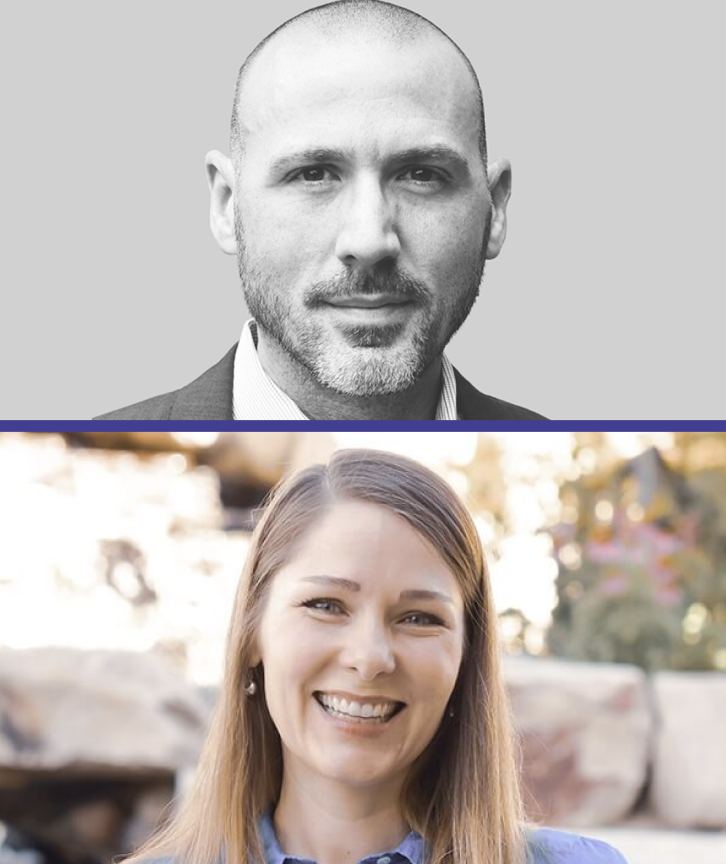

In this episode, Terryl Givens and Paul Reeve explore the history of the Church’s priesthood-temple ban that concluded in 1978.

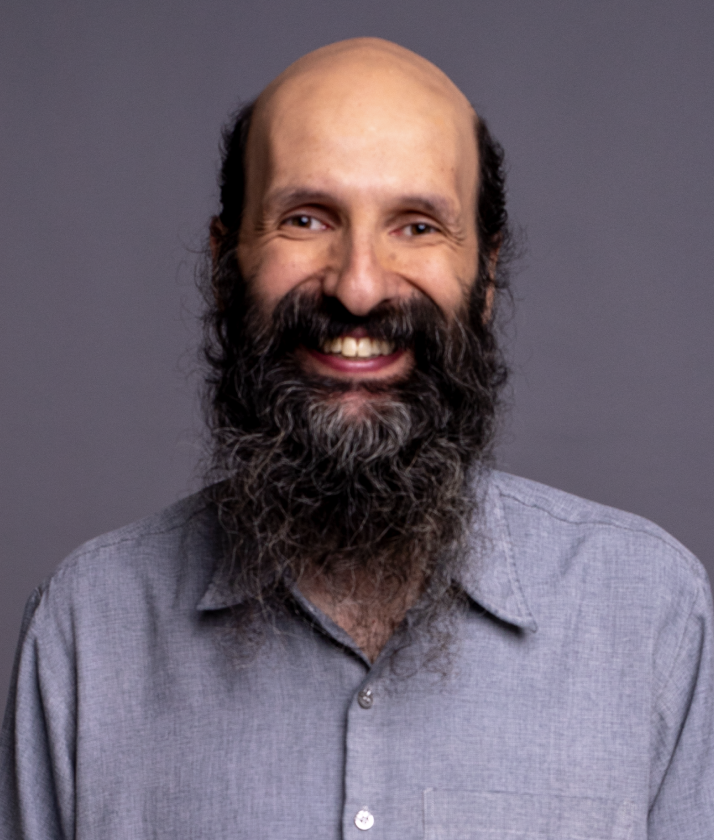

Paul is the Simmons Professor of Mormon Studies at the University of Utah. His award-winning book, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness, is considered by many as the best book written to date on the subject.

Dr. Reeve has also written a fantastic essay that addresses how to make sense of our history of denying priesthood and temple blessings to our Black brothers and sisters. It’s a fascinating read—and you really shouldn’t miss it. You can check it out for yourself here.

[podcast_box description=”The best way to listen to this conversation with Paul Reeve is on one of these podcast platforms:” apple=”https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/faith-matters/id1307757928#episodeGuid=Buzzsprout-4389509″ spotify=”https://open.spotify.com/episode/7v150DUIkue25you1BIcS3″ google=”https://podcasts.google.com/feed/aHR0cHM6Ly9jb252ZXJzYXRpb25zd2l0aHRlcnJ5bGdpdmVucy5wb2RiZWFuLmNvbS9mZWVkLnhtbA/episode/QnV6enNwcm91dC00Mzg5NTA5?ved=0CAkQ38oDahcKEwionO35xq3qAhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQAQ&hl=en-CA”]

In this episode, Paul and Terryl go both wide and deep on the priesthood-temple ban. Among other historical details, they discuss how the church was broadly criticized as being too inclusive in its early years—not white enough. This became a factor in Brigham Young’s 1852 decision to ban Black people from the priesthood and temple.

They also explore some of the explanations that developed in the church to explain the ban during its 126 year duration—and how each of these explanations have since been rejected and disavowed by the church.

We think this is an incredibly important and insightful episode. We suspect you’ll enjoy it.

Full Transcript

Tim Chaves: Hey, everybody. This is Tim Chaves with Faith Matters. In this episode, Terryl Givens and Paul Reeve, explore the history of the church’s priesthood temple ban that concluded in 1978. Paul is the Simmons Professor of Mormon Studies at the University of Utah. His award winning book, Religion of a Different Color, Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness is considered by many to be the best book written to date on the subject. Dr. Reeve has also written a fantastic essay that addresses how to make sense of our history of denying priesthood and temple blessings to our black brothers and sisters.

It’s a fascinating read and you really shouldn’t miss it. You can view it on our website at faithmatters.org. In this podcast episode, Paul and Terryl go both wide and deep on the priesthood temple ban. Among other historical details, they discuss how the church was broadly criticized as being too inclusive in its early years, not white enough. This became a factor in Brigham Young’s 1852 decision to ban black people from the priesthood and temple. They also explore some of the explanations that developed in the church to explain the ban during its 126 year duration and how each of these explanations has since been rejected and disavowed by the church. We think this is an incredibly important and insightful episode and we hope that you enjoy it.

—

Terryl Givens: Hello and welcome to another episode of conversations with Terryl Givens. I’m your host and visiting with us today is Professor Paul Reeve who is Simmons professor of Mormon Studies at the University of Utah.

Paul Reeve: That’s right.

Terryl Givens: Probably well-known to many for his important work, Religion of a Different Color published by Oxford University Press just a couple years ago.

Paul Reeve: 2015.

Terryl Givens: 2015 and time goes faster as you get older, you’ll discover Paul.

Paul Reeve: It does.

Terryl Givens: It won a few awards, didn’t it? I think it was the best book by the Mormon History Association and quite an impressive piece of scholarship. We’re here today to talk about a number of things, we’d like to talk about your book. In more general terms, we’d like to talk about race issues in the Latter-day Saint tradition. We want to talk about such things as the priesthood ban. We’d like to talk about its origin and history, a lot of people in the church are still unfamiliar with the specifics of that past. We’d like to talk about where we are as a church today and where we might be heading in terms of issues related to race and color.

Why don’t you start us out with just giving us a kind of good overview of the priesthood ban that was in place roughly from 1852 until 1978, more or less and let me just say a few things by way of preface to this particular conversation. Joanna Brooks published a book recently on Mormonism and white supremacy in which she made the claim early on in her book that there is still a pervasive amount of mythology in the Mormon community about the origins and the rationale behind the priesthood ban. So, that I think gives us one good rationale for trying to add some clarification and light to the subject today. Why don’t you just jump in with that?

Paul Reeve: Sure, well, I think it’s important to recognize that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is born into a fraught racial culture, the 1830’s issues about race and slavery are percolating throughout the United States and remember this is an American born faith. It’s really difficult to imagine that those questions wouldn’t then come to have an influence on the way that the early church develops. So, situate that against the fact that Joseph Smith claims, at least for Revelations where he articulates that this Gospel message is to be taken unto every creature. Latter-day Saints like to quote every nation, kindred tongue and people but I think every creature leaves no room for doubt.

Terryl Givens: Right, right.

Paul Reeve: This is universal.

Terryl Givens: Reinforced by Book of Mormon language as well, right?

Paul Reeve: Absolutely. Absolutely. It’s a universal gospel message and early Latter-day Saints seem to take that seriously. The first documented person of black African descent to join the faith is 1830 in Kirtland, Ohio. There have been black Latter-day Saints ever since. The missionary message went to every creature and they seemed to take that seriously. There’s no documented evidence of Joseph Smith ever articulating a racial priesthood or temple restriction.

Terryl Givens: What a great beginning.

Paul Reeve: It is a very good beginning.

Terryl Givens: Can we just end with that?

Paul Reeve: That’s a good place to end and I would say then, I see the 1978 Revelation as returning us back to those universal roots.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: Not something dramatically different.

Terryl Givens: It’s not a development.

Paul Reeve: No, it’s in fact restoring us back to where we started.

Terryl Givens: Yeah.

Paul Reeve: I think that’s an important way to think about our racial history, in fact is-

Terryl Givens: Now, that’s a new understanding though, right, because for some time it was taught and I think genuinely believed by most in the leadership, as well as the membership that the restrictive policies and ideology behind the ban went back to Joseph Smith himself.

Paul Reeve: That’s right and that memory I think, that false memory gets solidified at the turn of the 20th century and it becomes the new memory moving forward. It becomes entrenched in collective Mormon memory, in fact, to the point that it takes a revelation to get rid of in 1978.

Terryl Givens: Right. Can I just ask one question at this point? I was talking to one of the more preeminent LDS historians many years ago and he gave his personal opinion that the stature of Joseph Smith was such that he thought unlikely that any subsequent prophet would deviate from the pattern he laid down, unless there had been some intimations from Joseph Smith of movement in that direction. You find no evidence that that’s the case.

Paul Reeve: No, I don’t and maybe we should talk about a couple of things that I see at play as the open racial vision established under Joseph Smith, gives way to a race-based priesthood and temple restriction under Brigham Young. One factor you have to consider then is Latter-day Saints are participating in this open racial vision, outsiders looking in suggests that they are too inclusive of people that the rest of white society, know should be segregated and even enslaved.

Terryl Givens: This reminds me, I actually have a few excerpts here from your book that this connects to, you wrote the perception that Mormons were too inclusive earn them fear and scorn in a national culture that favored exclusion, segregation and even the extermination of undesirable races.

Paul Reeve: That’s exactly right. I mean, I think that’s a crucial context to keep in mind here. So, just one example in the state of Missouri, a newspaper article says that Mormons in the state of Missouri have opened an asylum for rogues and vagabonds and free blacks. They’re accepting all the undesirable people.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: It’s a collection of undesirables and that generates fear and concern especially in Missouri. Mormons have invited free blacks to the state of Missouri to incite a slave rebellion and to steal our white wives and daughters, fear of race-mixing in 1833, that helps us to account for the Latter-day Saint expulsion from Jackson County, Missouri. It begins with W. W. Phelps issuing an editorial to black Latter-day Saints. If you’re going to gather to Missouri, you have to understand it’s a slave state and the laws of Missouri govern your ability to move freely in this state.

You have to have papers that substantiate your status as a free black. He quotes two sections of the Missouri State Code, saying if you don’t have those papers, you’re subject to being whipped and expelled from the state. I don’t want my fellow black Latter-day Saints to experience that.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: Be aware, if you’re gathering to Zion, these laws govern your ability to move freely in this state and outsiders in Missouri read that editorial and say Phelps has invited free blacks to incite a slave rebellion. They scatter his press, destroy his building, drag a couple of Latter-day Saints in their town square and tar and feather them. That’s the beginning of the Latter-day Saint expulsion from Jackson County and it’s about racial issues. They also accused Latter-day Saints who invited these free blacks like I said, to steal their white wives and daughters, casting fear, projecting fears of race mixing onto Latter-day Saints. That just simply takes on a life of its own throughout the rest of the 19th century.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: Especially after polygamy has openly announced, outsiders imagine that Mormons are facilitating race mixing.

Terryl Givens: Now is there any movement in Joseph Smith’s language or writings or speaking as a result?

Paul Reeve: Yes, so in 1835 we have a section in the Doctrine and Covenants where Joseph Smith responds to this context by saying we as Latter-day Saints won’t baptize enslaved black people without permission from their masters and he instructs missionaries preaching in the South, don’t baptize enslaved people of black African descent without first converting their masters or permission. So, it leads to internal policies trying to respond to these accusations that are being leveled against them. Then, in 1836 that fear of race mixing really gets combined with a fear of the abolitionist movement. In the 19th century, if you were an abolitionist, anti-abolitionist accused you of really being interested in race mixing.

If you want to free the blacks what you really want to do is intermarry amongst them, because of the accusation that’s leveled against abolitionists.

Terryl Givens: They’ve leveled that, Lincoln, right?

Paul Reeve: Yes. In fact, the term miscegenation is crafted specifically in Lincoln’s 1864 re-election, the emancipation proclamation by his opponent is called the Miscegenation Proclamation.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: You’re freeing four million black people and what you’re trying to do is set them loose to intermarry and intermix amongst the rest of the population. What’s at stake isn’t just interracial marriage in their minds, democracy is at stake. Senator Calhoun has said on the floor of the United States Senate in 1848, “Democracy is the government of a white race.” He believed that people who were not white were racially incapable of participating in democracy. So, what you have to understand then as outsiders project those fears onto Latter-day Saints, they’re not merely suggesting that Latter-day Saints are a suspect religious group. They are a suspect racial group and American democracy is at stake.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: So, the stakes are really high as this contest plays out.

Terryl Givens: Take us to 1852 and what develops then?

Paul Reeve: Yeah, so before we quite get to 1852, let me just drop us into 1847 really briefly to say that it’s important to note that Brigham Young himself is also on record in 1847 as being favorably aware of a black priesthood holder. I’m saying that open racial vision is articulated even by Brigham Young as late as March 1847. So, as three years after Brigham … Excuse me, Joseph Smith has been murdered and Brigham Young is on record, referring to Q. Walker Lewis. It’s an interview that takes place in Winter Quarters in March of 1847. You have a black Latter-day Saint William McCary who’s complaining that he is not being treated fairly by Latter-day saints at Winter Quarters because of his race.

He’s probably right. He was experiencing racism and Brigham Young in that interview, as McCary continues to complain and says … McCary says, “Well I don’t have any positions of leadership or authority.” Brigham Young says, “Well, we don’t care about the color,” and to reinforce that point, he cites favorably Q. Walker Lewis as a black priesthood holder. “We even ordained black men to the priesthood,” he says. We have one of the best elders, an African in Lowell, a barber. That’s pretty much a direct quote from Brigham Young. Those attributes that he describes perfectly match what we know about Q. Walker Lewis.

Paul Reeve: He is a black man in the Lowell, Massachusetts branch who is a barber by trade and was ordained to the priesthood by William Smith who is an apostle at the time.

Terryl Givens: Joseph’s brother.

Paul Reeve: Joseph’s brother, yes, that’s exactly right. He is a functioning elder in the Lowell, Massachusetts branch. You have movement then from 1847 to 1852 with Brigham Young himself and I think it’s really a concern over race-mixing that you see Brigham Young’s position devolved from 1847, when he says, “We don’t care about the color,” to 1852 when he very much articulates a concern over race. That first open articulation takes place during debates in the Utah Territorial Legislative Session.

Terryl Givens: Some of this gets complicated because when is he speaking as prophet and when is he speaking as governor and …

Paul Reeve: It’s exactly right. Those roles heavily overlap in that legislative session. It’s an all Latter-day Saint legislative body and Brigham Young is prophet of the church, as well as governor of the territory of Utah. In one of his speeches he gives at legislative session, he basically says, there is no distinction between those two roles. Yes, no problem overlapping those roles and he says he has every right to come and dictate any matters spiritual and temporal to the legislative body and he’s really speaking against federal judges who have been appointed and some of them have run away because they say, you have this, an American theocracy operating and one of his speeches in 1852, he lambaste them.

Yeah, that complicates it and you have one legislator, Orson Pratt who is also a sitting apostle. His roles are also mixed between legislative and ecclesiastical and they’re butting heads in that legislative session, Orson Pratt and Brigham Young butt heads. They’re debating several bills. There’s an Indian Indenture Bill. There’s a black servant code, trying to define the legal relationship between white enslavers who have converted to the LDS faith and brought their black enslaved people with them to Utah territory. It’s important to note that some of those black slaves are also Latter-day Saints.

We’re talking about white Latter-day Saints enslaving their fellow co-religionists. What laws will govern that relationship? That’s one of the bills under debate and they’re also debating an election bill. Orson Pratt stakes out a position whereby he wants the law that will legalize slavery in Utah territory outright rejected.

Terryl Givens: That’s the law that would make the angels to weep.

Paul Reeve: That’s exactly right. He’s disgusted by the notion that Latter-day Saints would contemplate the enslavement of people who he calls innocent and he says there’s no reason to do so. It’s a free territory, why would we enact positive legislation to bring slavery where it doesn’t exist and he also points to the movement, the anti-slavery movement around the globe. I think he probably has the British Empire mind, where he says, “You know this is on its way out, globally, why would we enact it here?”

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: Like you mentioned, he says, it’s enough to cause the angels in heaven to blush. He’s horrified by the thought of introducing slavery but he doesn’t win that debate.

Terryl Givens: They passed legislation that legalizes, they call it servitude though, right?

Paul Reeve: That’s right.

Terryl Givens: It applies equally to whites as well as blacks, a kind of indentured servitude?

Paul Reeve: The first couple of provisions of the bill do and then the rest of the bill really apply to those who are enslaved. Really, it’s a bill that is aimed specifically at regulating white enslavers rather than the black enslaved. It’s very different from the kind of bills that were passed to regulate slavery in the south. Brigham Young really speaks out against chattel slavery, that he sees in the south but he also speaks out against immediate abolitionists that he sees in the North.

Terryl Givens: He’s trying to find the middle road?

Paul Reeve: He is.

Terryl Givens: It’s closer to northern legislation, right, and that it provides for eventual emancipation of-

Paul Reeve: Yeah, the bill that actually passes is a form of gradual emancipation. It’s a conservative form of gradual emancipation, meaning that it would free no one than a slave but it would not pass the condition of servitude on to the next generation.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: Pennsylvania, Kentucky … or excuse me, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, all passed forms of gradual emancipation and there are echoes I think of those bills in what Utah passes. The Pennsylvania bill for example, frees no one than a slave, children born to those enslaved would be called servants until age 28 and then they would be freed, right? Utah’s bill doesn’t have a clause that they have to wait until age 28. It just simply doesn’t pass on the condition to the next generation. The rising generation would be free. Those who are brought to Utah Territory as slaves would die as slaves. It’s a conservative form of gradual emancipation.

Terryl Givens: So, how do we transition from this then to the priesthood ban?

Paul Reeve: Well, as that debate is taking place, you had Brigham Young first publicly articulate a racial priesthood restriction. He will talk about a curse of Cain. He says that Cain killed his brother Abel and as a result all of Cain’s descendants who he understands to be people of black African descent, even though, we shouldn’t understand it that way, that’s a part of the cultural inheritance that predates the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by a couple of hundred years, it’s a part of the broader Judeo-Christian tradition where Jewish scribes interpreted, the Book of Genesis and that curse as being a black skin. So, that was just sort of common understand-

Terryl Givens: So, it’s just an appropriation of a Christian paradigm.

Paul Reeve: Exactly, right, he brings it into the Latter-day Saint tradition and gives it theological weight at this moment in 1852. He says that all of Abel’s descendants who, he understands to be white people will have to get the priesthood before Cain’s descendants can have the priesthood.

Terryl Givens: Now, it seems to me that at this moment, you’re already kind of insinuating into the theological rationale an allusion to a pre-existence, right, because you’re positing that there are these kind of spiritual categories, right, and some were going to come through the line of Cain and some were going to come through the line of Abel and we can’t allow one to be privileged over the other. So, correct me if I’m wrong but it seems to me that what’s happening is we’re finding a kind of perfect storm of circumstances that conduce toward the priesthood ban. On the one hand, you’ve got ready and available to you this Christian widespread belief and a black curse.

Paul Reeve: Yeah.

Terryl Givens: Mormonism adds to the mix a conception of a pre-existence, which seems to be tremendously important in what develops because going back to Plato in classical thought, going back to Origen in Christian thought, thinkers had always tried to come to terms with explanations for the disparity in the human family, of circumstance and race. Suddenly Latter-day Saints have this conception of a pre-mortal existence that they can appeal to, right, to explain differences in human opportunities and circumstance in this world. Then, the third ingredient that is added is the translation of the Book of Abraham which is coming to be widely disseminated and will eventually be canonized in 1880, which is easily misread as referring to a priesthood ban on descendants of Aegyptus, right?

Paul Reeve: Yeah.

Terryl Givens: You’ve got all these three circumstances conspiring to almost make a priesthood ban inevitable, given the way you read those three different factors.

Paul Reeve: Yeah, so let me just make some important distinctions and clarifications. For Brigham Young, what he articulates in 1852 is all granted in the Bible and this curse of Cain that he sees as his justification.

Terryl Givens: So, Orson Hyde will go to the pre-existence more explicitly but Brigham Young doesn’t?

Paul Reeve: That’s correct. Orson Hyde gives that as an explanation in 1845 not for priesthood restriction, just for-

Terryl Givens: Just the curse, the skin.

Paul Reeve: Yeah, where do we account for, where black skin comes from? He will articulate that. Brigham Young outright rejects in 1869 to the School of Prophets any notion that anyone was less valiant, neutral in the war in heaven, in the pre-existence.

Terryl Givens: That persists as a kind of underground mythology, will resurface later.

Paul Reeve: That’s right. That’s exactly right. Here’s how I understand it, I think Brigham Young establishes a theological pressure point that violates the second article of faith. Joseph Smith says, we’re held accountable for our own sins not for Adam’s transgression. Brigham Young will articulate a racial restriction that traces to the murder of Abel by his brother Cain and then holds people of black African descent, responsible for a murder they took no part in.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: So, that violates the second article of faith. The pressure point, to alleviate that pressure point and the explanation that will be articulated by others, never by Brigham Young. He will only use the Bible and the curse of Cain to explain this but to alleviate that pressure point then, you have others who will come back to this notion that people of black African descent must have been less valiant or neutral or fence sitters.

Terryl Givens: Orson Hyde all the way through B. H. Roberts

Paul Reeve: Yes. Well, it continues on into the 20th century. Joseph Fielding Smith, who will say not neutral but less valiant.

Terryl Givens: Right, distinction without much of a difference.

Paul Reeve: Exactly, right, that’s exactly right. It never goes away because you have that problem that Brigham Young establishes. It’s a violation of the second article of faith. Someone brings up neutrality in a war in heaven in 1869 to the School of the Prophets and Brigham Young-

Terryl Givens: Shoots it down.

Paul Reeve: Shoots it down immediately and immediately returns to curse of Cain. That’s the only explanation they’ll ever use and it’s also important to know that they never draws upon the Book of Abraham either, only the Bible. The Book of Abraham will start to be used by George Q. Cannon after it’s canonized in 1880, as another way of alleviating that theological pressure point.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: Those explanations will continue to percolate all the way through 1978.

Terryl Givens: Any intimation ever on the part of Brigham Young that there was any revelatory basis behind his pronouncements?

Paul Reeve: No. In fact, so what we see in the debate in 1852, by the end of his most … how do I put this, his most forceful speech it’s drenched in racism, it’s the 5th of February 1852 speech. He really stakes out a strong position. By the end of that he says, “I know people think I’m wrong,” and I think he’s referring to Orson Pratt, because we know that Orson Pratt gave a speech on the 4th of February, unfortunately that speech wasn’t recorded so we don’t know what he said.

Terryl Givens: No other voices that we know of besides Orson Pratt that were raised in protest.

Paul Reeve: Orson Spencer, strikes kind of a middle ground in his speech but unfortunately, the other speeches on this debate are not recorded.

Terryl Givens: Kind of like Adam Gohn, they all fall in line.

Paul Reeve: Yeah. We know that Orson Pratt is advocating for black male voting rights in 1852. So, that’s an important new piece of historical information to understand why Brigham Young says some of the things he says in his 5th of February speech. On the 5th of February … I imagine on the 4th of February even though Orson Pratt’s speech isn’t recorded, Orson Pratt is saying, no other prophet ever said this before. Brigham Young on a fifth of February, “If no other prophet ever said it before, I say it now, black people cannot hold a priesthood because of the curse of Cain,” is what he says.

He also says, “Black people cannot rule over me and use our territory, meaning we will not give them the right to vote and most horrifically we just as well give mules the right to vote as people of black African descent or Native Americans.” That’s Brigham Young at his racists worst but remember he’s responding to Orson Pratt. He was advocating for black voting rights and so he’s saying, “They won’t rule over me in this territory. They won’t have the right to vote and they won’t rule over me in this church, meaning they won’t have the priesthood.” Those two things are really animating the debate.

At the end of that speech, like I said, he also says, “I acknowledged that other people will disagree with me and they’ll say I’m not right but I know I’m right.” I’m only citing that to say he’s not saying thus saith of the Lord.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: He’s not claiming a revelation, the speech isn’t even published in the Journal of Discourses. It’s not published in the Deseret News. It’s recorded by George Watt. Watt will transcribe some of it but we’ve gone back to his original Pittman version and we’ll be publishing that in a documentary collection of that 1852 Legislative Session. I’m only saying, it was never canonized, never included in the Latter-day Saint scripture. If that’s the speech that anyone wants to claim as revelation, I say let’s publish it and let’s confront it, right, because it’s pretty horrific.

He says that he’s striking out on his own. If no other prophet ever said it. It’s a clear indication that I’m moving us in a new direction. I say it now, if no one said it before, I’m saying it now. He admits that he is moving in a different direction.

Terryl Givens: The next pivotal moment in this story, could we say around 1908, thereabouts when Joseph F. Smith, one of the leading figures who reinterprets those earlier developments and subsumes them within a larger narrative of a kind of continuous tradition from Joseph Smith, rather than seeing it as a Brigham Young innovation.

Paul Reeve: Yeah, that’s right and I think, there’s some … I would say the next really important moment is 1879 because you have a black priesthood holder, Elijah Abel who appeals for the right to be sealed to his wife.

Terryl Givens: Temple blessings.

Paul Reeve: To receive his endowment and to be sealed to his wife Mary Ann who’s also a black Latter-day Saint who passed away in 1877. He wants to have his love for her sealed in the temple and to receive his endowment. He received it, he’s washed and anointed in the Kirtland temple, participated in early baptisms for the dead in Nauvoo, then moved to Cincinnati, emigrated to Utah, baptized two additional times and then in 1879 appeals to John Taylor for his temple admission and to be sealed to his wife. I think 1879 is important because if you want to say that the racial restriction is unambiguously in place as late as 1879, why does the leader of the Latter-day Saint faith have to conduct an investigation over whether we allow Elijah Abel into the temple?

If it’s a set policy, whatever we want to call it, in 1879, why would it even then need an investigation and in fact, Taylor conducts an investigation. The results of that investigation is Joseph F. Smith is sent to interview Elijah Abel. Abel produces his certificates, claims that Joseph Smith sanctioned his priesthood. Joseph F. Smith comes back to the meeting, reports that, “Hey he’s a valid priesthood holder.” They allow his priesthood to stand but don’t allow him temple admission. You have the development of a temple restriction that coincide with the priesthood restriction.

Terryl Givens: So, priesthood restriction, 1852. Temple restriction, 1879?

Paul Reeve: Yeah, some people will say that Brigham Young is already restricting temple admission. The problem is it’s more belated remembrances. So, I haven’t found a contemporary document from the 1850s and 60s from Brigham Young but it’s later remembrances who say, “Well, I think Brigham Young said this.” He may have and Joseph F. Smith later remembers that Elijah Abel actually applied to Brigham Young first and Brigham Young told him no. If that takes place it doesn’t survive in that written record but what does survive is the 1879 account and John Taylor is still unaware of what to do. Elijah Abel goes on a third mission for the church in 1884 and returns, dies within two weeks of his return.

He’s in his late 70s and his obituary is published in the Deseret News. Whoever writes it is aware of the shrinking space for black Latter-day Saints. It’s not a typical eulogy. It basically is a recitation of his priesthood certificate dates. He died a faithful Latter-day Saint, in service to his cause, exercising his priesthood as a missionary. Here are his priesthood ordination dates. Then, we go to 1908 wherein, Joseph F. Smith erases from collective Latter-day Saint memory those black Latter-day Saints who complicates this white story. He falsely remembers back in 1908 that Joseph Smith declared Elijah Abel’s priesthood null and void, excuse me.

That false memory then puts the priesthood restriction in place from the beginning. It’s always been there. God put it in place. It traces back to the eternities. Human beings can’t do anything about it. That’s in my estimation, the last brick in this wall of priesthood segregation and temple segregation.

Terryl Givens: So, that’s the narrative, it becomes enshrined around 1908.

Paul Reeve: Yeah.

Terryl Givens: Endures without a hiccup until 1960s, would you say, is Lester Bush the first who seriously challenges that narrative about the past?

Paul Reeve: Yeah. Stephen Taggart before that, basically articulates the Missouri thesis, where he says it really wasn’t from the beginning but it developed as a result of the context we talked about in Missouri. Lester Bush then in his 1973 article says, no, it’s not even Missouri, it’s Utah Territory and it’s Brigham Young. So, you have then historians who are going back and investigating and saying, “Hey, that narrative doesn’t really hold up to historical scrutiny. There is no evidence to support the restriction being in place from the beginning.” That obviously challenges the existing kind of understanding and Lester Bush claims that he had evidence that Spencer W. Kimball read his essay. Now, I’m not trying to direct point-to-point dots but-

Terryl Givens: It seems to clearly have been a factor in his thinking.

Paul Reeve: A factor to reevaluate what the current assumptions were.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: Exactly, yeah.

Terryl Givens: So, let’s jump ahead to 1978, are we in a spot now kind of like the Catholic Church with limbo, where they recognize after a few thousand years … well, actually a thousand or so, that there wasn’t any papal kind of authoritative basis for what was thought to be a doctrine and we are in a kind of limbo, aren’t we? I mean what is the status of the priesthood ban in our present understanding?

Paul Reeve: Well, you have leaders like Bruce R. McConkie, within a couple of years, of the … excuse me, within a couple of months of the 1978 Revelation, who gives a talk at BYU, who says, “Forget everything I said or Brigham Young said or George Q. Cannon said. We were speaking with limited light and knowledge,” which seems to be an indication of the lack of revelatory knowledge as these racial restrictions were put in place and took on accumulating precedent across the course of the 19th century. That was never repeated in a general conference setting, never really taught in Sunday school or institute.

So, even though 1978 changed in terms of priesthood ordination, allowed black men and women to attend the temple, there really wasn’t a concerted effort to unteach the things that we’re taught.

Terryl Givens: The problem though isn’t just with the mythologies, right, isn’t just with the rationales behind the ban, the problem is also with the ambiguity surrounding the degree of inspiration and divine authority behind that ban, right?

Paul Reeve: That’s right.

Terryl Givens: This is the source of agony for many in the church, especially our black members. If I can just relate a personal anecdote, I’ve done informal surveys of members of the church in various settings where I’ve spoken, asking how many understand the gospel topics, essay on this subject to be an acknowledgment that the ban was a product of racist understanding of the era? Most members of the church raised their hand. I’ve asked the same question in settings where I’m meeting with CES employees and nobody raises their hand. The essay deliberately or not seems to be, a have been written in such ways to leave open the question of whether this was prophetic error or a long delayed but anticipated development in a revelatory process. Would you agree?

Paul Reeve: Yeah. I mean, it doesn’t definitively address that very question and so, it leaves that question lingering, I think in the minds of some people.

Terryl Givens: Any signs or hopes that we might find resolution in one way or the other?

Paul Reeve: Well, I really don’t know, I guess for me as a historian, what I see is the historical evidence does not indicate, this is of divine origin. I see it sort of taking on a life of its own and I see these important moments where each succeeding generation and willing to violate the precedent established by the previous generation even though Brigham Young violates the precedent established by Joseph Smith. What I … I guess what I more often than not see is, is sometimes those who don’t believe it as of divine origin, their faith is sometimes called into question by a fellow Latter-day Saints. I’ve experienced that myself.

Terryl Givens: Right.

Paul Reeve: It stinks. If you don’t like the message, sometimes you attack the messenger.

Terryl Givens: Well, let me … can I run a hypothesis by you that I think has tremendous bearing on what you’re describing? Latter-day Saints evolved in a Jacksonian culture were fiercely individualistic. One theologian said we have an obsessive concern with moral agency and individualism. We have a hyper Protestant sensibility but we operate within a hyper Catholic hierarchy. It seems to me that we confront fairly unique challenges with regards to matters of conscience. Kierkegaard wrote his most famous essay on the nature of the Abrahamic sacrifice, which he diagnosed roughly as a call to subordinate personal conscience and morality to a divine mandate.

That is why I think it was very apt to refer to polygamy as an Abrahamic test, right? Mormons had to learn how to quiet their personal revulsion for this marital practice, in deference to what they saw as a prophetic authority. Would it be fair, do you think, to suggest that that may have been one of the factors that paved the way for such horrors as the Mountain Meadows Massacre, where a group of good faithful Latter-day Saints, in deference to local authorities felt they had to quiet their moral revulsion at what they were asked to do, in order to embark on this massacre of innocent migrants.

I’ve wondered if something similar is at work in the anguish that so many people have felt and continue to feel over a priesthood ban, where our sensibilities are appalled at this racial differentiation and yet we’re wedded to this conception of prophetic authority that has culturally evolved into a notion of prophetic infallibility and hence, the impasse.

Paul Reeve: Yeah, I think that’s a fabulous way to articulate it. I think that’s what’s at stake for some people. I taught primary for five years and primary kids love to march around the room, singing, “Follow the Prophet.”

Terryl Givens: Yeah.

Paul Reeve: I understand, I value being in a religious tradition that has a prophet. The first principle of the gospel is faith in Jesus Christ, not faith in Brigham Young or Thomas S. Monson or Russell M. Nelson. There’s a reason for that. So, I hope that we are also willing to allow prophets to be human. I love D&C section one, what’s articulate as the Lord’s preface to the Doctrine and Covenants. It was given as the preface to the book of commandments which evolved into the Doctrine and Covenants. We tend to cherry-pick a couple of verses out of that section.

I think if we understand it in its full complexity, I sort of imagine the Savior sort of thinking back over the long span of human history and the previous dispensations and thinking about Moses maybe killing an Egyptian and hiding his body in the sand and then later called as a prophet. Thinking about Judah who sleeps with his daughter-in-law. David and Bathsheba. Peter who denies knowing the Savior.

Terryl Givens: In fact we don’t get any examples of infallible authorities in the scriptures that I’m familiar with.

Paul Reeve: Our scriptures are just replete with these kind of examples.

Terryl Givens: Yeah.

Paul Reeve: I imagine the Savior sort of taking a deep breath and saying, “Okay I need to prepare this last dispensation,” and if you look at the verses there in D and C section one, he says, “Your leaders will be weak. They will be prone to error and they will sin.” Weak, error-prone, sinners. It’s a great description of me. I am on a stumbling journey with God and I identify with Latter-day Saint leaders who are struggling themselves and attempting to do the best with what they have and when we put them on such a high pedestal, I think we sometimes do them and us a disservice.

I more readily identify with the Savior’s articulation of our leaders as weak error-prone sinners who despite their weaknesses and error and sin, accomplish some pretty important things. Then, he goes on to say, well, this is the only true and living church, speaking in other church collectively, not individually. You could be led by weak, error-prone sinners and collectively as a body of believers you are true and living. We leave out the way that he articulates who his servants will be in the last days and I think we do ourselves a disservice in the process. I think it’s okay to let them be human.

I don’t believe that God told Brigham Young to say what he said. I believe when he makes a prophet a prophet he does not revoke a prophet’s agency and if a prophet has agency, a prophet can make mistakes. The foundation of the plan that we talk about is grounded in agency and yet we act like when a prophet becomes a prophet, God is the puppet master and the prophet is the puppet and that violates the very foundation of our plan. So, Ezra Taft Benson has an apostle, articulated what he called the Samuel Principle. He uses obviously the Old Testament to articulate this principle.

It’s a talk he gives in 1973 I believe, whereby he says well, the children of Israel is asking for a king. God tells them no. They keep complaining and finally He says, “Okay Samuel they haven’t rejected you. They rejected me. Give them a king and let them suffer the consequences.” It was 400 years of a monarchy. Those are really grievous consequences and Elder Benson at the time said, “Sometimes He gives us what we want and lets us suffer the consequences,” so think about the last 116 pages of the Book of Mormon. Think about the Kirtland Safety Society. Why didn’t you simply tell Joseph Smith don’t found the darn bank.

It’s going to fail and you’re going to go through this period of apostasy where people are going to call your prophetic mantel into question. Save yourself the trouble because he lets us make mistakes and I believe he let Brigham Young say what Brigham Young said and let us suffer the consequences and I think we’re still dealing with those consequences and I think it’s white Latter-day Saints who continue sometimes to reassert notions of white supremacy and sort of the rightness of those old racial teachings without sort of thinking through their implications, who continue to bear the consequences of those decisions. I think understanding-

Terryl Givens: Those are hard words because the consequences of a few individual’s misjudgments can be appalling and yet it seems to me that that should just serve to emphasize the centrality of those baptismal covenants, that if our lives were completely centered around mourning with those who mourn and comforting those in need of comfort and lifting the burdens of the burdened, then we would all be addressing this problem as a collective.

Paul Reeve: Yeah, I love that and that’s why I feel like understanding our own racial history is really important. If we understand the way that Latter-day Saints were racialized at the hands of others, if it can happen to even seemingly white Latter-day Saints, right, if racism can be brought to bear against seemingly white Latter-day Saints, their whiteness called into question.

Terryl Givens: In fact, the Harvard Encyclopedia of Ethnic Groups identifies us as a separate ethnic category, so it was a successful process of racializing Mormons in the 19th century.

Paul Reeve: That’s right and the most significant way you claim whiteness for yourself is in distance from blackness and I see that helping-

Terryl Givens: That’s one of the pressures.

Paul Reeve: I see that helping to explain the racial restrictions, right? So, if we can understand the way that that took place in the 19th century, understand our own racial history, my hope would be as you articulate, a willingness then to stand in places of empathy for other groups who are experiencing much more severe racism of their own in the 21st century, why can’t we use our racial past as a motivator to fulfill our baptismal covenants, to stand in places of empathy and mourn with those that mourn and recognize what racism looks like, be willing to look through someone else’s eyes because we’ve experienced the pain of rejection in our own racial past.

Nowhere to the degree that African-Americans have experienced, I never want to make that kind of claim. That’s not what I’m suggesting. I am suggesting that our history can serve as a profound motivator for us to stand in places of empathy for the racism that we see taking place today and turn our fraught racial past into a positive racial future. We should be at the forefront of speaking out but we need to understand our own racial history to then be willing to stand firmly and say, “Hey, we look … we know what it looks like to experience it from the outside and then we also know what it looks like to participate in it from the inside, both of those things are not good. Let’s stand in a firm place to move us forward into claiming that universal gospel that Joseph Smith launched when he launched this religious movement.”

Terryl Givens: Paul, thank you for your work as a historian of the Latter-day Saint past, helping us to so much better understand our history and thank you for your wise words joining with us today.

Paul Reeve: My pleasure thank you.

Terryl Givens: Thank you very much, so long.

—

Tim Chaves: Thanks so much for listening and a special thanks to Paul for coming on to talk with Terryl and to everybody who’s left a positive review of our podcast or content on any platform, we really do appreciate it. We read each review and comment and are grateful for the encouragement and for helping get the word out about Faith Matters. We hope everybody is staying healthy and safe and as always, you can check out more at faithmatters.org.