The Latter-day Saint racial story is best understood in three phases:

Phase 1. Open priesthood and temples to all races. Phase 2. Segregated priesthood and temples. Phase 3. Back again to open priesthood and temples for all races.

For this story to make sense one must first understand the illogical and fluid racial context within which the Restored Church was immersed.

“Whiteness” in American and among the Latter-day Saints

These three phases played out against a nineteenth century racial context which placed Anglo-Saxon “whiteness” at the top of a racial hierarchy and denigrated everyone else–including those who may have looked white but whose behaviors were viewed as deviations from Americans’ ideas of whiteness (e.g. Irish and Italian immigrants). It’s difficult to overstate how subtly pervasive this idea of “whiteness” became in 19th century America.

The overarching arc of the Latter-day Saint racial story, thus, goes from Mormons being denigrated as not white enough in the 19th century, to Latter-day Saints being perceived as too white by the 21st century.

In the 19th century Latter-day Saints felt compelled to claim whiteness for themselves. The most significant way to do so was to distance themselves from blackness. Latter-day Saint leaders thus developed racial priesthood and temple restrictions designed to distance themselves from blackness and secure their whiteness.

Racial culture’s influence on the early church

It is impossible to divorce the racial history of the church from its American context. Being white meant a person had access to social, economic, and political power that people who were deemed not white–or in the case of the Latter-day Saints, not white enough–did not have.

In 1790, for example, the very first US Congress stipulated that to be a naturalized citizen in this new nation a person had to be free and white. Thus, by happenstance of birth, a person with white skin was given access to citizenship while someone born with black or brown skin was denied citizenship. In 1848, Senator John C. Calhoun, in fact, argued on the floor of the United States Senate that “democracy is the government of a white race.” He believed that only white people were capable of democracy. Laws, supreme court decisions, and other policies and practices across the course of US history reinforced these ideas.

Latter-day Saints initially resisted the American racial culture, but eventually began to adopt and participated in it.

Within this fraught racial culture, Joseph Smith announced a universal gospel message designed to gather into its fold peoples of all races and ethnicities, no exceptions. Joseph Smith received at least four revelations instructing him that “the gospel must be preached unto every creature, with signs following them that believe” (D&C 58:64; see also 68:8, 84:62, 112:28). “Every creature” indicated that no one was to be excluded. The Book of Mormon reinforced this idea when it described the universal reach of Jesus Christ’s atonement, “Hath he commanded any that they should not partake of his salvation? Behold I say unto you, Nay.” (2 Nephi 26:27).

At least some early Latter-day Saints took these commands seriously. The first person of Black-African descent, a formerly enslaved man named Peter, converted in 1830 in Kirtland, Ohio, and there have been Black Latter-day Saints ever since.

In 1835, William W. Phelps declared that all people were “one in Christ Jesus . . . whether it was in Africa, Asia, or Europe.” The following year Ambrose Palmer, the presiding elder at New Portage, Ohio ordained Elijah Able, the first Elder of African descent, on 25 January 1836. Joseph Smith, Jr. acknowledged the ordination with his signature two months later.

Able received washing and anointing rituals in the Kirtland temple and performed baptisms for the dead at Nauvoo. Able moved to Cincinnati before the Nauvoo temple was completed but the Nauvoo newspaper declared in 1840 that it anticipated “persons of all languages, and of every tongue, and of every color; who shall with us worship the Lord of Hosts in his holy temple, and offer up their orisons in his sanctuary.”

As late as March 1847, three years after Joseph Smith’s murder, even Brigham Young is on record as favorably aware of Black priesthood ordination. In response to complaints from Black Latter-day Saint William McCary about the racism he experienced at Winter Quarters, Brigham Young insisted, “We don’t care about the color.” When McCary persisted, Young cited Q. Walker Lewis as evidence that Latter-day Saints did not discriminate even in priesthood ordination. “We [h]av[e] one of the best Elders[,] an African in Lowell—a barber,” Young said, referring to Lewis, a Black abolitionist ordained to the priesthood by apostle William Smith, Joseph Smith’s younger brother.

How did outsiders view the Latter-day Saints’ open racial vision?

Most outside observers at the time were convinced that Latter-day Saints were too inclusive of people whom the rest of white society knew should be segregated or even enslaved. Protestant white Americans leveled a string of allegations against Latter-day Saints that suggested that they were violating racial norms.

Mormons accepted “all nations and colours” into their religious community one newspaper complained. Other observers also noted that Mormons violated racial boundaries. One said that Mormon elders preaching in the South maintained “communion with the Indians,” and walked out with “colored women.” One outsider suggested that Mormons honored “the natural equality of mankind, without excepting the native Indians or the African race.” Worse still, Missourians protested that Mormons “opened an asylum for rogues and vagabonds and free blacks” and even promoted black “ascendancy over the whites.” These were not celebrations of Mormon diversity, but accusations that Latter-day Saints violated an established racial hierarchy.

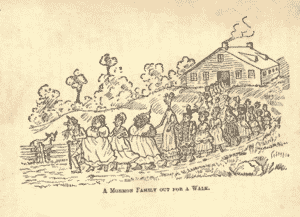

Especially after 1852 when Latter-day Saints openly announced the practice of polygamy, outsiders imagined race mixing as one negative ramification of their “barbaric” practices. Monogamy, they argued, was the preserve of the white race. No true Anglo-Saxons would practice polygamy or surrender their free will to the despots Joseph Smith and Brigham Young. Mormons therefore were deemed not white. One medical doctor even argued that polygamy was giving rise to a new degenerate race in the Great Basin. As outsiders viewed it, Mormon polygamy was not merely destroying the traditional family, it was destroying the white race and making it unfit for democracy.

Figure 1: John D. Sherwood, The Comic History of the United States, 1870. This illustration offers one of many examples of how outsiders imagined Mormon polygamy to include race mixing. Notice the African-American wife, the Asian wife and the Native American or Pacific Islander wife.

How did the priesthood and temple restrictions develop over time?

As outsiders consistently conflated Latter-day Saints with other undesirable racial groups (e.g. Black people, Native Americans, Chinese immigrants) as a way to call their whiteness into question, Latter-day Saints began to distance themselves from their own Black members. That process began under Brigham Young and was first publicly articulated in 1852 in two speeches he gave to the Utah territorial legislature. It took on a life of its own after that. Each succeeding generation of leaders was unwilling to violate the precedent Young established, even though Young had himself violated the precedent of open male ordination which Joseph Smith instituted.

In 1879 John Taylor added a temple restriction when he barred Elijah Able from receiving his endowment and being sealed to his wife, even though Taylor allowed Able’s priesthood to stand. In 1908, Joseph F. Smith solidified the restrictions in place when he falsely remembered that Joseph Smith had nullified Able’s priesthood and that the restrictions had thus been in place from the beginning.

Joseph F. Smith’s reconstituted history became the new memory for the new century. In this version of LDS racial history, priesthood and temples had always been white. Twentieth century leaders created a narrative that suggested that Mormonism’s racial priesthood and temple restrictions were in place from the beginning. God had put them there. This counterfactual narrative ignored the practice of open ordination established under Joseph Smith and effectively shrouded the priesthood and temple restrictions in the foggy mists of time, stretching back to the eternities.

Even still, it is a mistake to view the priesthood and temple restrictions as universally understood or firmly in place even after 1852. Elijah Able’s son Moroni was ordained an elder on his deathbed in 1871 and his grandson, Elijah R. Ables, was ordained in 1935, although he had passed as white to qualify. The Elijah Able family thus included three generations of priesthood holders. Their family story demonstrates the impossibility of policing racial boundaries.

What explanations did Brigham Young offer for the restrictions?

Brigham Young offered one reason, and one reason, only for the restriction. He claimed that it originated in Cain’s killing of his brother Abel. Because Cain killed Abel, Young said, God marked him with “the flat nose and black skin” and cursed him from the priesthood. All of Cain’s descendants (Black people, according to Young) would have to wait until all of Abel’s descendants received the priesthood before they would be eligible for ordination. He did not draw upon the Book of Abraham, the Book of Mormon, or the Book of Moses–only a problematic reading of the Bible. His explanation also clearly violated Joseph Smith’s Second Article of Faith, that humankind would be accountable for their own sins and not for Adam’s transgression. Young’s explanation held Cain’s supposed descendants accountable for a murder in which they took no part.

As a result of the contradictions embedded in Young’s justification, some LDS leaders suggested a different explanation: that Black people were neutral/fence sitters/less valiant in the pre-mortal life and therefore were born into a cursed linage.

In 2013, in an official Race and the Priesthood essay, the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve Apostles adamantly disavowed all such explanations given in the past.

Why do the stories that we tell about the priesthood and temple restrictions matter today?

The stories that we tell, especially those that continue to justify the prior restrictions, matter because they continue to “arrogantly assume” as President Gordon B. Hinkley articulated it, that a white man was “eligible for the priesthood whereas another who lives a righteous life but whose skin is of a different color is ineligible.”

The stories that we tell matter because when we perpetuate a false racial history we perpetuate racism. The stories that we tell matter because evidence matters, and to suggest that the racial and temple restrictions were in place from the beginning is to argue against undeniable evidence to the contrary.

The stories that we tell matter because to argue that the racial priesthood and temple restrictions began with a revelation is simply false. Where is the revelation we are supposed to believe started the restrictions and supposedly indicate that it was God’s will? Can we read it? There is only one revelation in the LDS scriptural canon on race and priesthood, and it came to Spencer W. Kimball and the Quorum of the Twelve in June 1978. It restored the faith to its universal roots and officially ended its 130-year quest for whiteness.

The stories that we tell matter when they lead us to perpetuate a subtle form of racism. Some suggest that that the gospel was intended for “white people first and then black people” in parallel to Jesus’ New Testament injunction to preach to “Jews first and then Gentiles.” This suggestion is easily discounted.((This justification ignores the fact that Jesus healed the daughter of the Greek woman (“a Syrophenician by nation”) when she asked for the crumbs from the table (Mark 7: 24-29) and that Jesus testified to a Samaritan woman at the well that he was “the Christ.” He then stayed among the Samaritans two days and as a result “many more believed because of his teaching.” The converted Samaritans soon testified that “this is truly the Savior of the world” (John 5: 26, 40-42). More importantly, as Paul explained, the Jews had no priority in righteousness or merit, for “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Romans 3:23). No group or ethnicity was superior to any other, “for there is no difference between Jew and Greek, for the same Lord is Lord of all” (Romans 10:12). The same was true in the 1830’s when apostle Parley P. Pratt professed his intent to preach “to all people, kindred, tongues, and nations without any exception” and included “India’s and Africa’s sultry plains” in a poetic expression of his global dream for the Latter-day Saint message. The notion that the gospel would be taken in stages—whites first then blacks, in parallel to Jews first then gentiles—is patently false and historically inaccurate.))

Others suggest that Christ, in His wisdom, knew it was “not black people’s time yet.” “They” were somehow not yet quite ready for the gospel message. Pause for a moment to realize the degree of racism embedded in the suggestion that it was not “their” time yet. It assumes that all black people are the same in some fundamental way. That for some reason, because of their skin pigmentation, they, as a group, were excluded from Joseph Smith’s declaration that the gospel was to be preached to “every creature.” Rather than seeing Black people as individual sons and daughters of God in need of Christ’s grace, this idea suggests that black people should be seen, based only on the color of their skin, as not quite capable of accepting and living the gospel. These ideas must be recognized as the very essence of racism.

These ideas also erase from history Black Latter-day Saint pioneers. These ideas ignore the fact that Black people have been a part of the Latter-day Saint movement from its founding year to the present. They ignore the fact that people of Black-African descent received the priesthood and temple rituals in the first two decades of the faith. They ignore the fact the Black Latter-day Saints, such as Jane Manning James, Green Flake, John Burton, and Oscar Crosby were 1847 pioneers into the Salt Lake Valley (Flake, Burton, and Crosby were enslaved Latter-day Saints when they entered the valley). They were not only ready to hear the gospel message but they responded to its call with baptism and then trekked across the continent enslaved to fellow church members. John Burton was born into slavery in 1797 in Virginia and is buried in Parowan, Utah, where he contributed $15.00 (a significant sum at the time) toward building the first church in that frontier community. Burton’s sacrifices matter, and to suggest that he and other Black pioneers were somehow not ready for the gospel message erases their contributions to Latter-day Saint history and it erases their faith.

The stories that we tell matter because sometimes Latter-day Saints are still more invested in protecting Brigham Young and other leaders from their statements on race than they are in defending our Black Latter-day Saint brothers and sisters against racism. Do we really believe that Brigham Young is somewhere in the eternities upset that we are not defending his racial position from 1852? Surely he knows now why the Book of Mormon so emphatically testifies that “All are alike unto God…black and white…” Surely Brother Brigham has moved well beyond his 1852 racism and is urgently hoping we will do the same.

The stories that we tell matter because skin color is not a curse, nor was it ever a curse, and to suggest otherwise is to perpetuate white supremacy. To suggest otherwise is to suggest that white is normal and other skin tones are a deterioration away from normal. The stories that we tell matter because the lives of Black people matter to Christ. As believers in Christ, it is our obligation to see the diversity of God’s family, celebrate its cultural, ethnic, and racial differences, and ensure that our brothers and sisters in Christ are treated “all . . . alike.”

But don’t we find racial discrimination justified in scripture?

Racism is wrong no matter where it is found or who engages in it. If a prophet engages in racism, whether that be Brigham Young, Joseph F. Smith, or Nephi, it is still wrong. We need to allow prophets to be human and to learn from both their wisdom and their mistakes. Not all scripture is meant to be affirming. Some scriptures are meant to teach us the consequences of bad ideas and behavior by God’s people (the Old Testament is full of such examples).

So what about seemingly racist verses we encounter in the Book of Mormon? One approach is to read them metaphorically. Marvin Perkins and Darius Gray offer guidance in their Blacks in the Scriptures discussions.

If you are more prone to take Nephi and his references to a “skin of blackness” at face value, then consider that Nephi himself may have been demonstrating racial bias, describing his siblings in racial terms. It is possible that Lamanites had intermarried among surrounding indigenous groups and Nephi viewed such mixing as a racial and cultural deterioration away from his desire to preserve an Israelite heritage. (As the church’s official Book of Mormon and DNA Studies essay notes, “The Book of Mormon . . . does not claim that the peoples it describes were either the predominant or the exclusive inhabitants of the lands they occupied. In fact, cultural and demographic clues in its text hint at the presence of other groups.”) Even still, it is important to remember that Lehi’s family would have been of Middle Eastern origins and as a result not “white” themselves.

In any event, racism is wrong, even (perhaps especially) when a prophet engages in it. One overarching, unspoken message to be taken from the Book of Mormon (especially if you are prone to read notions of dark skin and curses literally) is that racism is a fatal sin. The Book of Mormon calls all our racial (and racist) assumptions into question. In the end, the supposedly lighter-skinned Nephites are wiped from the earth by the darker-skinned Lamanites–a fitting annihilation of self-righteous notions grounded in nationalism and white supremacy.

What purposes did the restrictions serve?

If you are still of the mindset that “God must have had his reasons” for implementing the racial priesthood and temple restrictions, then what purposes did those restrictions serve? What did they accomplish?

The Prophet Joseph Smith said the gospel was to be preached “unto every creature,” but in 1908 Joseph F. Smith instructed missionaries to “not take the initiative in proselyting among the negro people.” In this case, the restrictions forced the church into a violation of its own scriptural imperatives. The racial temple and priesthood restrictions served to ensure that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was known as a white church. But the price of whiteness for Latter-day Saints was high–and we are still paying it.

Some people suggest that conforming to American racial norms and prejudices was necessary for the Church to survive. However, the same year, 1852, that Brigham Young articulated a racial priesthood restriction, the church openly acknowledged that its members believed in and practiced polygamy. Polygamy brought considerable scorn from the nation and did not end until the federal government nearly ground the church into dust. Yet LDS leaders willfully stood against the crush of derision for what they believed to be a divine principle. Why would conforming to racial prejudices be necessary for the Church to survive, but conforming to prevailing marital norms (monogamy) not necessary?

Latter-day Saints love to quote Joseph Smith’s Standard of Truth from the Wentworth Letter, wherein he says that “no unhallowed hand can stop the work from progressing.” So, no “unhallowed hand can stop the work from progressing” and yet treating Black people equally would have?

The restrictions more pointedly did not even work. Sure they kept the majority of black men from priesthood ordination and black men and women from temple admission, but others slipped through the sometimes porous walls of exclusion, especially as several generations of mixed racial marriages meant that some LDS families eventually passed as white.((Sarah Ann Mode Hofheintz’s father was Black and her mother was white. She is the earliest known person of Black-African ancestry to receive temple admission. She was endowed in the Nauvoo Temple and later sealed to her white husband in Utah. Some of her white Latter-day Saint descendants in the twenty-first century still exhibit African ancestry in their DNA. See: https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/hofheintz-sarah-ann-mode))

Nelson Holder Ritchie is one example. He was born into slavery and eventually converted, along with this white wife, Annie Cowan Russell, to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1909 Nelson and Annie were denied temple admission because their bishop told Nelson he had “negro blood in him.”

Annie’s and Nelson’s children, however, all received priesthood ordinations and temple admissions before June 1978 because they passed as white. Nelson’s grandson, Rex Olson played quarterback for Brigham Young University in the 1940s and his other descendants received priesthood ordinations, temple marriages, and served missions. Seventy-two of Nelson’s descendants in the twenty-first century have completed DNA tests which show African ancestry.

The priesthood and temple restrictions were meant to prevent any person with African ancestry—no matter “how remote a degree”—from temple and priesthood admissions. It was a racial policy that DNA evidence demonstrates was impossible to enforce. So, what purposes did the restrictions serve? If the one drop policy was the standard, then DNA evidence demonstrates that there has never been a period in LDS history without people of Black-African descent who held the priesthood and attended the temple.

What can we learn from all this?

Racism is intoxicating and racism mixed with religion can be particularly pernicious. The Latter-day Saint message has always included a universal foundation. “All flesh is mine” Jesus told Joseph Smith in 1831, “and I am no respecter of persons” (D&C 38:16). It also included universal male ordination which stipulated that “every man” who embraced the priesthood “with singleness of heart may be ordained and sent forth” (D&C 36: 7). A Savior who claimed “all flesh” as His own and flatly declared that He was “no respecter of persons” clearly would not originate racial restrictions that contradict His very nature. Yet Latter-day Saints sometimes continue to lay the racial restrictions at Jesus’ feet as if the “natural man” was never involved in their formulations and perpetuations.

It is much more profitable, in my estimation, to learn from our collective history, rather than defend or deny it. What lessons can it teach? Latter-day Saints experienced racialization at the hands of outsiders; and Latter-day Saints engaged in racism on the inside. What better people to lead out on issues of racial inequality and social justice? Rather than be hobbled by our past racism, what if we owned it and used our shared history to stand in places of empathy? What if we were willing to work against racial injustice because we experienced a soft form of it? What if we were willing to speak up and stand up against systemic racism because we engaged in it ourselves and have come to understand its consequences? What if we were willing, like Jesus, to claim “all flesh” as our own?