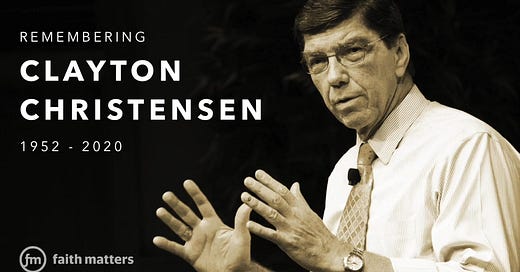

Harvard Business School Professor Clayton M. Christensen died on January 23, 2020, and he left a remarkable legacy. He was a monumental figure in both the business and academic worlds, as well as in the Latter-day Saint community. He was the father of five children and author of at least eleven books. But to those who knew him, Clay wasn’t just a thought leader or a world-renowned professor or an influential Church member — he was a mentor, confidant, and friend unlike any other.

In this episode, we spoke with Efosa Ojomo, Kyle Welch, and Barbara Morgan Gardner to share thoughts and memories of Clay.

Efosa first met Clay during his time as an MBA student at Harvard. Along with Karen Dillon, Fos was the co-author of Clay’s final published book, The Prosperity Paradox.

Next, we talked to Kyle Welch, a Professor in the business school at George Washington University. Kyle became close with Clay well during his time at Harvard as a doctoral student from 2009 to 2014.

Our final interview is with Barbara Morgan Gardner, a Professor at Brigham Young University, and author of the book The Priesthood Power of Women. She got to know Clay when she did post-doctoral work at Harvard and as she served as an Institute Director in Boston.

00:57 How Efosa met Clay

11:42 How did Clay share his faith?

22:25 How Kyle met Clay

30:36 Kyle’s favorite stories from Clay

34:30 How Barbara met Clay

42:47 Clay’s lasting impact

Listen on Apple Podcasts:

Listen on Google Podcasts: https://podcasts.google.com/?feed=aHR0cHM6Ly9jb252ZXJzYXRpb25zd2l0aHRlcnJ5bGdpdmVucy5wb2RiZWFuLmNvbS9mZWVkLnhtbA&episode=QnV6enNwcm91dC0yNjkyMjE5&ved=0CAIQkfYCahcKEwiQtujyvcPnAhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQBQ&hl=en

Listen on Spotify:

Share this post