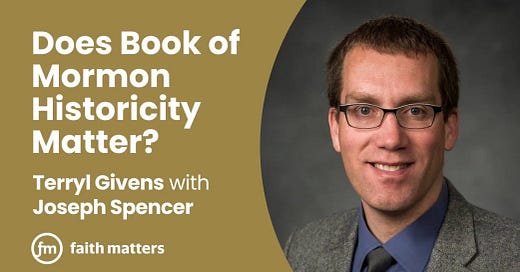

In this episode, we’re diving into one of the questions from our Big Questions series: Terryl Givens invited Joseph Spencer, a philosopher and professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University, to talk about the question of Book of Mormon historicity.

The claim that the Book of Mormon is a translation from ancient plates written by Hebrew people who immigrated to the American continent has been challenged from its first publication, and conclusive confirming evidence has been equally controversial. So what is at stake in either affirming or questioning the historicity of the Book of Mormon as the modern translation of an ancient record? Could it be some other form of inspired writing? Or must we accept the book as being exactly what it claims to be? How do we deal with seeming challenges to its historicity?

Joseph Spencer is prominent among a new generation of Book of Mormon and Biblical scholars. He is the editor of the Journal of Book of Mormon Studies and the author of eight books, including “1st Nephi: A Brief Theological Introduction” published in 2021 by the Neal A. Maxwell Institute.

You can find more from our Big Questions series by clicking on “Big Questions” from the main navigation menu — and watch out for much more Big Questions content as we move throughout the year.

Thanks as always for listening, and we really hope you enjoy this conversation with Terryl Givens and Joseph Spencer.

Share this post