“Catholics teach that the Pope is infallible, but nobody believes it. Mormons teach that their prophet is fallible, but nobody believes it.”

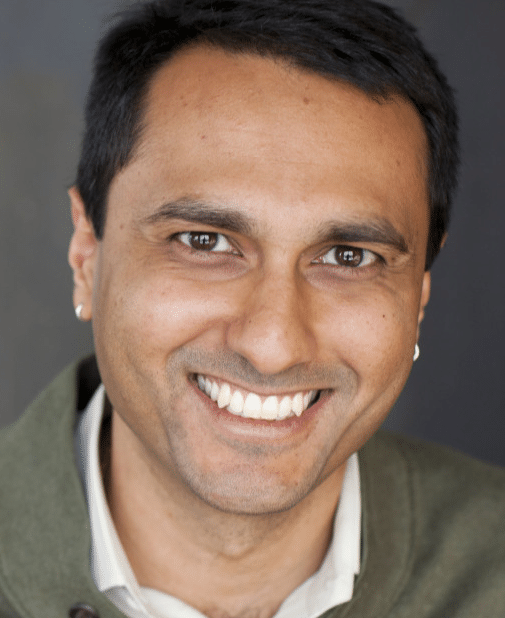

In this video conversation for the Faith Matters Big Questions series, we speak with Patrick Mason (Dean of the School of Arts & Humanities and Professor of Religion at Claremont Graduate University) about the role of prophets and church leaders as divinely called yet imperfect men and women and how we can trust and sustain fallible leaders.

We cover topics like the priesthood-temple ban, Prop 8, the role members play in affecting the Church as part of the body of Christ, and a faithful but discerning approach to sustaining church leaders while following one’s own conscience.

We hope you enjoy this conversation!

For more Patrick, check out his book Planted on Amazon. You can also check out our resources on learning from imperfect Church leaders for more answers to our Big Question, “In the past, church leaders have made some significant mistakes. How much should I rely on pronouncements and teachings of our leaders today?”

Kate: Well, welcome to this video chat podcast conversation with Faith Matters. Faith Matters, to give a little context, I think if you’re listening to this you may know, but Faith Matters is … Our aim is to create a community that’s able to explore and expand to view of the restored Gospel, to consider things, and discuss things, and I think a lot of us are thinking about, and talking about, so this provides a platform to do that. This specific conversation is a part of the Faith Matters Foundation’s Big Question series. This series is where we answer questions that we get from Latter Day Saints.

Kate: Often these questions are questions we’ve had ourselves as contributing members of Faith Matters, and also that we’ve heard from other members of the church. That’s the kind of the context that this conversation fits into. My name is Kate and I help facilitate these conversations, and have these discussions, which is really meaningful for me. I want to introduce Tim Chaves, who is with us. He is also a big contributor to Faith Matters, and our work that we do.

Kate: Tim is a BYU alum, go Cougs, and also went to Harvard Business School. He’s a tech entrepreneur, and an integral contributor to our team. We’ll be able to hear from Tim a little bit. Thanks for being with us.

Tim Chaves: Yeah, my pleasure.

Kate: I also wanted to introduce Patrick Mason, who is with us. I was telling Patrick earlier that I’m kind of a fan [inaudible 00:01:39] of his work. I guess to introduce Patrick a little bit, you may know him, he’s the author of an incredible book called Planted: Belief and Belonging in an Age of Doubt. For me, this book was in some ways a pioneering experience for me, just because it was one of the first books, or some of the first content I was exposed to in regard to doubt, and how that fit into our faith. It’s an amazing book. Patrick is also currently, and correct me if I’m wrong on any of your LinkedIn facts, but currently the dean of arts and humanities at Clermont. Clermont is a school in California.

Kate: Actually I have a friend who goes there, and it’s a pretty prestigious private graduate school. I hear, Patrick, that you may be taking a new position closer to the mountains. Am I right about this?

Patrick Mason: That’s true, yeah. I’m moving [from 00:02:36] the Utah State University this summer.

Kate: What about this? Wait, no, not … Wait, Utah State? There are so many Utah schools.

Patrick Mason: Yeah, not the University of Utah, Utah State University in Logan.

Kate: [crosstalk 00:02:48] I had the big U up for the wrong school. Utah, so we’re speaking in Logan, correct?

Patrick Mason: Logan, yeah, exactly.

Kate: Wow, that’s … Are you excited to be in Utah?

Patrick Mason: Yeah. I mean, I’m from there, I’ve got family there, and tons of friends, and I’m really looking forward to it.

Kate: Cool. Well we’re excited to have you here in Utah. Okay, well we’re happy to have you here, Patrick. Thank you.

Patrick Mason: Thank you. Thanks.

Kate: We’re excited to hear your thoughts. Today we’re going to explore an essay that Patrick wrote for Faith Matters Big Questions project. The essay will be available on our website, faithmatters.org. The essay that Patrick wrote it about the fallibility of prophets, which is something … it’s a pretty big topic I think right now, and in general, and it has been, and so we’re excited to talk about this idea of how we frame prophets in our understanding of faith, and our understanding of our membership in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, and how that all fits together.

Kate: We’re excited to discuss that. The essay, it will be an interesting read that will be on our website for the listeners to check out. With that, Tim, why don’t you talk about the quote that we [crosstalk 00:04:10] earlier in Planted.

Tim Chaves: Yeah. Patrick, in your book Planted, you relate the joke that goes, Catholics [inaudible 00:04:19] to the Pope is infallible, but nobody believes it. Mormons teach that the prophet is fallible, but nobody believes it. To the extent that that’s true, and that culturally at least we do have this general idea … Even though we specifically that we don’t believe in the infallibility of prophets, there is a sense that we sort of place this air of infallibility on our leadership, and to the extent that that’s true, how did we get here? You’re a historian. What’s been sort of the background leading up to where we are as we approach this issue right now?

Patrick Mason: Yeah, that’s a great question. I think that we sort of wrestle with it culturally, because in some ways we’re kind of willing to admit that leaders in the far distant past occasionally made mistakes. Right?

Tim Chaves: [crosstalk 00:05:12].

Patrick Mason: I think we can wrap our minds around the fact that Brigham Young maybe made some mistakes. We probably don’t know very much about most presidents of the church. Actually, how much does anybody know about George Albert Smith, right?

Tim Chaves: [crosstalk 00:05:26].

Patrick Mason: It’s hard for us to kind of apply that consistently across the board. Then we become very uncomfortable talking about it with current or recent presidents of the church, essentially the ones in our lifetime. It’s really hard to talk about. How did it come about? My sense is that it began really early on, and it began by anti-Mormons essentially setting the agenda for us, that one of the very earliest attacks on Joseph Smith … Actually in the first major anti-Mormon book, it was called Mormonism Unveiled, they went and they did research with people that knew Joseph Smith growing up, and Palmyra, and with the Smith family, and they came back with these reports that they were kind of lazy, [inaudible 00:06:12], that they were involved in folk magic, and this and that.

Patrick Mason: It was a bit of a smear campaign on the Smith family. The message was, aha, he can’t possibly be a real prophet if in fact he has feet of clay, if he’s just kind of a normal human being with all of the foibles and frailties of any other sort of typical frontier family. That was an agenda set by these anti-Mormons, these opponents to Joseph Smith, and the early Latter Day Saints. I don’t think that it was a very theologically astute argument, because all they had to do was open their Bible, and find lots of prophets who had feet of clay. Nevertheless, that was the argument that they made. To be honest, the saints took the bait, and they responded by defending fiercely the character of Joseph Smith, and all of the other prophets, in sort of equating the two.

Patrick Mason: That if God called a prophet, then that prophet must be a special human being. I think we … I understand why. You want to be loyal to your friends, you want to be loyal to your leaders. Joseph Smith was unfairly charged for a lot of things. I understand that the very human impulse to want to defend your friends, but I think we sort of took the bait, that took us down a road that wasn’t necessarily actually theologically very productive for us. I think that sort of then set us up since then.

Kate: What’s interesting about that … Thank you for sharing that. What’s so interesting is that it feels like we unknowingly fell into a perspective that’s really based on semantics. In some senses from what you say is maybe we didn’t clarify what we meant by prophet in some senses, or maybe that’s simplifying it too much, but that the anti-Mormon literature, what was released or that bait that we were given was, this is what it means, this is what you can expect. Then it was like okay, okay, that’s what we’re going to expect. In a lot of senses, and I think we do this as humans, we unknowingly fell into that definition.

Patrick Mason: Yeah, even though The Lord Himself wanted to keep us out of the trap. In section one of the Doctrine and Covenants, which obviously was not the first section revealed, but The Lord wanted it to be placed first so it’s the preface to the Doctrine and Covenants, it has a very strong doctrine where The Lord is talking about the prophets, and He says that He will work through the weak things of the world. I mean, it’s like right there at the beginning of the Revelations in section one, where God is trying to keep us away from any notion of [prophetoletry 01:04:26], or prophet worship, to say that, hey guys, the story’s about Me. The story is about the restoration of the Gospel, the story is about the redemption of Jesus Christ.

Patrick Mason: I used prophets to accomplish My ends, and to accomplish My will, the same way that I use all human beings. He calls the weak and the simple. It’s a remarkable doctrine, and a strong doctrine that we have prophets and apostles, but The Lord, right at the beginning of the restoration is saying, “Hey guys, don’t fall for this,” this idea that the prophets are sort of super human in some way, or transcend mortal probation with the propensity to sin in error.

Tim Chaves: Do you feel like we continue to fall into that trap today? Or is it more of, that’s our heritage, we’ve brought it down through the generations and continued to do it, or are there similar things happening today, and that’s how we like to [inaudible 00:09:55] etc …?

Patrick Mason: No, I think it’s definitely a cultural and historical inheritance for us that’s been passed down. Also, look, I mean we … Our faith, and our beliefs, and our church have continued to be the objects of ridicule at times, and sometimes for self inflicted wounds, but often times for other people looking in and not understanding, or for taking pop shots. There has been a strong sense of loyalty, of sort of closing ranks circling the wagons, and so there’s that part of it, the kind of social psychology of the group that sometimes feels persecuted. We can’t admit any weakness to the outside world, we can’t admit any flaws or any errors, because then they’re just going to latch on to that. I think that’s part of it.

Patrick Mason: Then the other part of it is that we don’t want to water down, or dilute the remarkable doctrine that God has called prophets and apostles. We don’t want to go on the other side of the spectrum and say, “Oh, you know what, prophets, it’s not that big a deal anyway.” We’ve struggled to kind of find that middle path in which we can boldly affirm the doctrine that God has called prophets and apostles, without turning them into something that they’re not.

Kate: What I think that begs the question for me as I’ve gone through my own journey of understand the doctrine of prophets, specifically in my personal life, I think we can speak of things as prophets, and what do you we think about this, but really, it affects us personally if you are a member of the church, or if you’re not. Going through this conversation and identifying, okay, what is a prophet not. A prophet is not perfect, a prophet is not expected to be. I think for me that begs the question of what is a prophet then, and I think you’ve touched on that a little bit, but really for me, grappling with this idea of okay, if a prophet is not someone to be worshiped, or exalted, or even that everything a prophet says is … I don’t know, I hesitate to use the word perfect, over use that word, but if that’s not what a prophet is, then where do I put a prophet?

Kate: I don’t know if we have necessarily answers for that, but I’d be interested in, how do we create a healthy relationship with this idea of a prophet, and is that as a guide, or is it as … I mean, for you, how have you kind of identified that relationship?

Patrick Mason: For me, it’s … I think that’s a great way to frame it, so both what a prophet isn’t, but then we also have to come up with what a prophet is, because in talking about prophetic fallibility, there’s a danger there too, of leaving sort of nothing … that’s there nothing left. I mean, if you peel away these layers, is there anything at the center of the onion. I want to affirm that there is, and so what do I think a prophet is? I think a prophet is really … especially in our modern church, and I think there’s some differences with Old Testament prophets, but in our modern church, I think really a prophet is … They are three things. They are servants, they are messengers, and they are witnesses.

Patrick Mason: All of those things are … exist in relationship to the person that they serve, the person whose messages they give, and the person that they’re witness of, and that’s Jesus Christ. I like to think of it that we don’t look to the prophets, we look through them to Jesus Christ, who is the real object of our worship. Prophets are essential. The only things that I know about Jesus Christ have been mediated through prophets, either ancient or modern. What do I know about Jesus Christ? It all came through the New Testament, through people who wrote witnesses of Him, who were His apostles, and who witnessed of Him.

Patrick Mason: I’ve never met Him. I have no direct unmediated knowledge about my Lord and Savior. In terms of His life, His atonement, those kinds of things, that all came through prophets and apostles. The same in the modern age. The things that we know were mediated through prophets and apostles, so I’m incredibly grateful for this gift, but again, I don’t want to focus on them, because I recognize that their role is as servants, as witnesses, and as messengers.

Tim Chaves: Interesting. Now I’m curious too because when I think about … I think when I was maybe much younger, and hadn’t thought about this too much, I thought of prophets as receiving instructions or revelationary inspiration in a way that’s really different than the way we, as rank and file members of the church receive it. To use an analogy, I would imagine prophets get sort of these direct, divine text messages that have explicit, clear instructions. In the mean time, we are sort of just like wandering around, and occasionally getting nudged in a direction you feel like, okay, that’s my inspiration, that’s my revelation.

Tim Chaves: I think if you look at it historically, there’s an argument to be made that prophets too are being nudged in a particular direction, and don’t always have that divine text message. You could look at mistakes that prophets have made, or sort of a correlation between the context and times that that they were in, and the decisions that they were making. If prophets are receiving revelation by nudge, just like we are, rather than by text message, how is it that they are able to be those special witnesses? How is that different than us receiving a confirmation about the reality of Jesus Christ, or of God’s existence, or anything really?

Patrick Mason: It’s a great question, and I’m not sure I know fully the answer to that. I think it’s a question about what does that special mean, in special witness.

Tim Chaves: Yeah.

Patrick Mason: We can recover … There are some statements by even current apostles, that sort of make it sound like that their witness is not qualitatively different than mine. I mean, they certainly have much more experience than I do. They’ve been at this a lot longer, and so I trust that their spiritual sensibilities are more refined, and deeper than mine. I think we also have this false sensibility that they hang out with Jesus in the temple. I just don’t think that’s true. I don’t think that they have like a red phone to the Celestial Kingdom. Again, we could pull lots of statements from them where they essentially say the same thing, that their process of inspiration is very similar to that of the rest of us.

Patrick Mason: There is something about the calling, which I think is special. We all experience this. If you’re a relief society president, you know that you get different kinds of revelation that you did before you were relief society president. This is one of the claims we make in this church, and it’s remarkable. It’s hard to articulate. It’s hard to even put your finger on, but we’ve all … Those of us who have been active in the church, and served in callings, we know this is true. If you served a full time mission, you know that you had a special kind of inspiration that you probably didn’t in your civilian life.

Patrick Mason: I think God honors the calling. When I hear special witness, I hear because that’s a special thing to be called by God, to lead His church.

Kate: Something that I thought of, Tim, when you were saying your nudge versus text message analogy, which I actually really resonate with, is I would even add to it, I think that I also have that belief that revelation to a prophet was extremely clear, full of clarity, full of … Seriously, Jesus in the celestial room, like, all right boys, this is what I think needs to happen. Here we go.

Patrick Mason: Here’s the font size and everything.

Tim Chaves: Yeah, exactly.

Kate: 100 percent. Not only in nature of how that revelation came, but I think to add to that, something that I grappled with was not only the form that that revelation came in, but the importance of revelation. I think for a long time I felt that God spoke to me about, if I needed to, the type of cereal to eat, or who to date, or these different things, but on big issues like who’s allowed to have the priesthood, and who’s allowed to be together, you know, those big who’s allowed to, a lot of those questions, or a lot of, I don’t feel good about this, or I don’t know about these big, deep, heart and soul questions. I think for a long time I felt were off limits to me, because I didn’t have that special calling.

Kate: Not only was I maybe not in the place to get the text message, but the text messages that I was getting, or the nudges that I was getting were in some ways of lesser nature, or I had a hard time trusting that I was allowed to get revelation, or receive revelation from God, that was important … I don’t know if important’s the word, but important or serious in nature, and that I had to just trust what I heard, which I don’t think is bad. I don’t think that trust or that confidence … I feel that deeply in a lot of our leaders, but I think that’s another part of that, is for me, letting go of that idea that I couldn’t, but embracing that I could also talk to God about those things.

Patrick Mason: So I sense that you felt like that revelation may be about doctrinal things, or something, that was somebody else’s job, and you were supposed to just get revelation about your personal life?

Kate: Yeah, totally. Not only someone else’s job, but that it was hard to trust … I think this is still the case to be honest, I think it can be really hard to find peace with feeling a certain way between you and God about something that maybe contradicts, or is slightly different from what we’re hearing. I don’t know if we need to go too deep into that, but it is an interesting experience to figure out how much do I really take charge of my agency, and my ownership in receiving revelation.

Patrick Mason: That’s a huge question I think. It does get into the really sticky issue of what if my revelation doesn’t line up with their revelation, and what if I’m feeling something really strongly that doesn’t seem to be 100% in line with them. I think that’s where we’re afraid to kind of have the conversation, where … I think that’s one of the toughest things, because I think we have developed almost no resources to really talk about that, in a really serious way. What happens … Not when just like you think something different, or where your politics are different, or something like that, but if really truly, The Holy Spirit that you have recognized, and that has taught you all the other gospel truths, that you’ve cultivated in learning to listen to The Holy Spirit.

Patrick Mason: What if that same sensibility puts you in a slightly, or maybe significantly different place on a particular issue. Let’s appeal just to history, ’cause it’s always safer. What if you were a member of the church before 1978, and you felt your revelation said to you, you know what, this policy/doctrine isn’t right. What do you do when that happens? That is a really tough …

Tim Chaves: Yeah, especially because we teach not only that we have the light of Christ, which we sort of equate with our conscience, but that we’ve … if we’ve been baptized, and received the gift of The Holy Ghost, that we actually have a guiding spirit that is able to teach us the truth. We feel like, I think, and we’re taught that if we pray, and are humble, and study, then we can receive revelation on things for ourselves. It can be really tough when you feel like, I came to something, and the prophet came to something else, and this is a zero sum game. There is not a way to make those line up.

Tim Chaves: I think what … I was just reading this chapter in Planted actually, Patrick, and you say, “There are no rules for what to do in every case, only principles to apply with the assistance of The Spirit. We find ways to balance faith, patience, grace, forgiveness, integrity, conscience, community, and covenant.” I think for now, I’m not sure there is a better answer than that, and I wish there were, but it’s looking at all of the obligations, all of the responsibilities, all of the inspiration, all of the experience that we have, and that others have, and trying to balance each of those things in each case, and I think it’s tough. I think it’s strenuous. I think it’s uncomfortable. I’m not sure, and maybe that’s a good thing.

Tim Chaves: Maybe when God set the wheels in motion with this whole thing, that’s what He intended, for us to have that struggle.

Patrick Mason: Yeah, I’m glad you read that quote, Tim, because I think sometimes we can reduce our faith in the prophets to the hardest thing about it, or our biggest disagreement, whatever that might be, historically or contemporary, and forgetting that actually there’s been a pretty stable core over nearly 200 years that has led us to where we are now, in terms of the core teachings of the Gospel of Jesus Christ that I think they are called to be messengers and witnesses of, in terms of the atonement, the restoration, God’s love for us, and the role of the Gospel in our lives.

Patrick Mason: I think we can become so hyper focused on that really strenuous thing. It’s not to marginalize or trivialize it one bit, but it’s so important to think about as you just said, all of the commitments that we have, and all of the experiences we have, and think about it holistically.

Tim Chaves: Yep. I’m curious. I think there’s this idea out there that maybe prophets are imperfect, but a lot of times, not when they’re acting in their official capacity. When they’re speaking over the pulpit, or when they’re acting in that official capacity, they’re really speaking for God, and there are no mistakes. One context that I think about that in is the priesthood temple ban, and I think there’s this idea out there that for reasons beyond maybe what we understand, that that was right for its time, and for the hundred and … I don’t know, 128 years that it was around, that was God’s will even though obviously we believe that God loves all of His children equally. I’m curious, Patrick, does that reasoning resonate with you? Would we say, because that was sort of so official, it must have been right? Do we need to find a way to make that work or are we okay and comfortable saying that was not right, that was wrong and eventually we figured it out?

Patrick Mason: I think it’s a terrific question, Tim. There are a lot of people in the church who I’ve talked with, who I respect deeply who hold that view, about the priesthood temple ban, that something so significant, something that shaped the history of the church and our ability to minister to such a large percentage of God’s children, something like that could not have happened without, in some way shape or form, God having a hand, or at least a finger in it. Right?

Tim Chaves: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Patrick Mason: Again, this is a view that’s held by a lot of people who I really deeply respect, and so I respect that view because of that. It’s not the view that I have, and so I feel like I can honestly and even maybe faithfully disagree with that view, partly as a historian, because there is actually no historical evidence for anything like a revelation that got the ban going, so partly I lean on the tools, and what we know from the historical evidence. Also, I think it’s entirely possible to think theologically about a way that even something so significant, that the church could still be true in its fundamental aspects, and yet nevertheless be in error, even for a very long time.

Patrick Mason: There’s language in the Scriptures about the church being condemned for various things. For instance, it’s neglected the book of Mormon. Actually President Benson talked about that when he became president of the church after 1978, and he says, “The church is still under condemnation for neglecting the book of Mormon.” That’s an amazing statement. President Benson said that for over 150 years, the church have been in condemnation for neglecting the book of Mormon, but nevertheless was still the true church. I think it’s entirely possible for us to think about ways in which the church could be in error on a particular issue, not on its core witness of Jesus Christ, and the restoration of the Gospel, and still be true.

Patrick Mason: Again, I think honest people can disagree about this, but I do think there’s a way to think about this in a faithful way, and still believe that that ban was not instituted or sanctioned by God.

Kate: I think just a question, and of course perspective, I think that evokes this follow up question for me, of if that could be the case, that the church is in error on a specific issue, and not on that underlying one is, but maybe on a specific issue because of … that that’s bound to happen at some point. For me that brings up this question of … I don’t think there’s an answer to this. At least if there is, I don’t know it, but what then do we do? When we may happen to fall on the other side of the issue?

Patrick Mason: Yeah again, what do you do if you’re a member of the church before 1978, and you feel not only through your own conscience, but through your revelation that the policy or doctrine is wrong? I personally believe that as much as possible, you try to stay with the church, and focus on the 99 other things that are right, rather than the one, even if it’s a really big one. At the same time, I have to admit I can’t fault … I know of a number of people, both African American and Anglo, who once they learned about the ban, especially when they were investigating the church, they decided that they couldn’t join the church. It’s hard for me to fault that view.

Patrick Mason: I would hope that those at least … That’s where people who are investigators, who hadn’t yet had a lot of … a lifetime of rich experience with the church, and so that issue … I can understand how it becomes … just overshadows everything else. One would hope that for people who have been in the church for a long time, that they’re able to weigh things in the balance, and recognize all the other gifts, and truths, and experiences that they’ve had within the church, that can counterbalance that one thing that deeply troubles them, and that they can look at it holistically.

Patrick Mason: Again, it’s very hard, and I think it’s a good philosophical question, at what point does that one thing … does it in some way undermine the other things. At least in this case, I think there’s a way for us to exercise discernment, and kind of separate some of these things, and focus instead on what is our core witness, why are we members of the church, and what do we think the church really is.

Kate: Yeah. I think thinking can they coexist, can this [crosstalk 00:31:51] I have, and this faith and connection to the church, can they coexist with each other. It’s a hard question, but I think you’re right, a good debate to have with God.

Patrick Mason: Right.

Tim Chaves: Yeah. I’ve heard Terryl Givens use the term faithful provocateur, which has always resonated with me. I think there is a way, and … For example, within Sunday School, within your ward members that you talk to outside of church, within your own family, I think you can teach principles that you believe in, you can point to the … I think especially on socialist issues, like with the up and coming generation, this is on a lot of our minds, and I think you can point to that big tent version of the church that you hope for. At the same time I think you can remain faithful in your callings, you can continue to serve in your ward and your community.

Tim Chaves: In a lot of ways I think those things that you do to be faithful and serve, they’re what give you the credibility to maybe push things just ever so slightly in the direction that you hope you might see the church go one day. That’s my approach at least.

Patrick Mason: Yeah. I think you can continue to absolutely affirm the principle and doctrine of living prophets and apostles that God has called, even while sometimes disagreeing with them. Again, we do this with our bishops all the time.

Kate: And ourselves.

Patrick Mason: Yeah, and ourselves. Yeah, I mean I can say, “I’m doing my best as a disciple of Christ, and guess what, I got something wrong today,” or yesterday, or I get some things really wrong, or I raised my hand and I sustained my bishop and my state president, and then you know guess what, I really disagree with them on some things. There’s a way that we do this and we experience it, we model it at the local level, and so I think it just becomes a kind of mental, and theological, and spiritual exercise for us to scale that up, and think about what does that look like at the prophetic level.

Patrick Mason: We have lots of examples throughout the history of the church where presidents of the church taught things from the pulpit, and the membership of the church just kind of shrugged. I think of blood atonement. I mean, Brigham Young, all the kinds of things that we say, what makes for a prophetic and authoritative teaching, so was it from the pulpit, was it in his office as a prophet, was it taught repeatedly. Blood atonement is one of those doctrines it’s like, check, check, check, all of those things that should have made it an authoritative doctrine of the church.

Patrick Mason: Brigham Young got this for years and years. He wouldn’t let go of the dang thing. The membership of the church really just shrugged. I mean, a few people sort of got on board, but for the most part they were like, nah, that’s not really us. No, but thanks, Brigham. There’s a kind of authority of the membership of the church that gets exercised in that way, when The Spirit just does not testify to the rest of the body of Christ, of that one thing, even if it’s strenuously taught by a prophet over the pulpit. This is all a kind of balance in terms of the way that these things play out.

Kate: I wonder too as I’ve thought about this, and as you guys are speaking about this, it really does push me to think about … and I don’t want to get too tangential in this idea, but to think about that God’s purpose for us truly, I think in the church, in our various communities, and our families, and our relationships, across any … ‘Cause really, all things are relationships, we’re in a relation to something, at least in my [inaudible 00:35:37] view of the world, and I think our relationship with prophets, and our relationship with the church, although sometimes inconvenient in its reality of frailty, I think that that inconvenience and that frailty in some ways may push us to engage with God in a deeper way than we may have otherwise.

Kate: In those moments of, I’m receiving deep revelation about something that’s pretty serious for me, that maybe is contrary to what I’m hearing from the church, or what I’m hearing … not even maybe from the prophets, but from a lot of members, or whatnot, that that dissidence in some ways I think can engage us in a process of turmoil, but also of deep growth, of this idea that in some way, that process can push us away from the laziness that is an easy trap to fall into.

Kate: I don’t mean to say that … Yeah, hopefully I’m just saying what I mean to say with that, but that that process … I don’t know if I know the end of that, but is in any sense we’re meeting the goal growth, which truly is in my mind, pretty paramount. I think that’s-

Patrick Mason: It is going to be uncomfortable sometimes. In sacrament meeting today I heard somebody … the speaker read a quote from Elder Neal A. Maxwell that I’ve heard before, but it goes something like, “If we’re really serious about our discipleship, there will be moments in which we are tested in really hard ways, the ways that force us to stretch the most, in whatever that is.” I think that’s really true, that I don’t think that over the course of our lifetime, and certainly not over the course of the eternities, that we’re ever going to get there just by being on cruise control. We’re going to have to throw this thing in manual at some point, and really kind of navigate, and figure out what this means for us.

Patrick Mason: That’s when you have to dig deep, and really think about, what do I believe. It’s a combination of heart and mind. I think if we leave it only to our mind, we’re not going to be open to all the ways that The Lord has to speak to us. If it’s all heart and if we close off the mind, then I think we’re shutting off one of the ways that God communicates with us too. It’s gotta be a combination of those two things. There will be moments where not just your faith is tested, in the sense that we all have adversity, but actually you really gotta figure out some of this stuff for yourself, in ways that nobody else can really give you an answer. Even a video chat from three very intelligent people, in some ways you’ve gotta figure it out on your own.

Tim Chaves: Yeah. I think what’s interesting … A question that that sort of brings up for me, is obviously there is a huge amount of personal growth that could come through that kind of a struggle, but I wonder about too, if you are going through that, is there a responsibility that members have to help the church through growth as well? Or is that responsibility purely on the part of our leaders and prophets? I’m sort of betraying what I think about this a little bit here I think, but if you look at the course of history, for example, the priesthood temple ban, I don’t think that the change to that policy that happened in 1978 happened in a vacuum. You know? I think it would be … we’d be discrediting the activists, and members of the church who are praying, and maybe fighting is too strong a word, but who are pushing for things to change, if we said this was just a lightning bolt.

Tim Chaves: I think at some point, I mean part of that struggle is not just growing ourselves, but figuring out, is there a way for me to help push the church forward as well. I’m curious what you think I guess about that.

Patrick Mason: I think one thing is I don’t want to make a distinction between me and the church. I am the church. You are the church. We are all the church, and the body of Christ. Now granted, we don’t all … the church does have a kind of vertical authority structure. We understand the way that the priesthood leadership works, all the way up to the first presidency, and to the president of the church, but I take very seriously my membership in the body of Christ, and that I have obligations to it, and that I have to own it in a really serious way.

Patrick Mason: Yeah, I think we’ll all find different ways to do that. We’ve heard from the pulpit periodically that the church is not a democracy, and that’s true. We don’t determine policy or doctrine through parliamentary procedures and things like that, but I do believe that changes come … I mean, the phrase that I like to use is The Spirit moves upon the waters. It’s sort of intangible, and it’s mysterious, even maybe a little bit mystical, but when there’s a sense of unrest in the church, when there’s a sense that there’s a kind of critical mass, or even maybe just critical yeast of members of the church who for whatever reason, some doctrine or policy isn’t sitting well with them, and they seek to genuinely, authentically, and faithfully wrestle with this, I think that’s when we open ourselves up, not just individually, but as a people, to God, to take us into a new place.

Patrick Mason: That all sounds kind of vague, and I know it is. We could look at different moments in history, you have cited 1978, I think you’re exactly right, and we could look at other moments in history too where there was something going on, and it was a shared effort, both kind of from the bottom up, and from the top down.

Kate: I love those thoughts. I think one, you saying it’s … I don’t like to separate myself and this idea of the church. I found for a long time a lot of my healing for my personal struggle, or faith journey, or transition, or whatnot, a lot of that healing came from reuniting myself with that idea. Instead of this idea of the church, and me as a little person below it, who knows how I’m even allowed to be involved in this, or there’s this meta power of men to be … [inaudible 00:42:39] as a woman, and kind of reuniting myself with the idea of the body of Christ, which felt like a healthier way for me to identify my unity with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

Kate: I really value that thought. I also value the idea of really having to expand our definition of those things, and expand ourselves in a way that that vagueness that you touched on, or that kind of meta ideas, I think in a lot of ways pushes us to say, “Not everything is black and white.” There are a lot of things, but I struggle or I have dissidence, or the prophet says this, or this is brought up in general conference. Can I still go to my ward? Can I still contribute? How do I maintain this relationship? This is just my thoughts, and I think you spoke maybe a little bit to this, but this idea that it’s okay to expand ourselves a little bit, and sit with that uncomfortableness, and continue to contribute to the body of Christ, because Christ is perfect, but the body of Christ is full of us, and that is a different story.

Kate: I appreciate those thoughts. Something I want to hear from you about, I think there’s in this conversation, a lot of ways that we can discuss this topic, to maybe make sense or make peace of it in our minds, and how we define things or whatnot. Something that for me a lot of previously, and you know, still probably exist in some sense for you, but previously a lot of my dissidence with my church membership, or with understanding the role of prophets, had to do with some deep experiences of betrayal that I felt in relation to the beliefs that I was taught growing up, that later as I kind of re-sifted through them, felt like wow, that was not healthy, or that was not good.

Kate: I grew up in California, and was pretty involved with Prop 8. That was a pretty strong experience of that. I think the church has shifted a lot of things in that context, but still, that sense of betrayal, I think that sense of pain, that sense of hurt and distrust, was a wound for me. We can talk about this in reframing, and all those things, but I don’t think that that necessarily heals those wounds, fully. Maybe I think it contributes for sure, but I’m wondering, for a long time I had a hard time finding peace with that, and repairing that relationship of trust, because from a psychological … I mean, I studied psychology, I studied relationships, and that relationship with leadership was damaged for me.

Kate: I think that that is an experience that some people have. I’m wondering your experience, and maybe to speak to that.

Patrick Mason: Yeah, no, thanks for sharing that. I have to say that I’m glad I didn’t live in California in 2008.

Kate: Yeah, it was hard. I will not lie. It was very hard, and still it is sometimes because [crosstalk 00:46:02]-

Patrick Mason: I moved here in 2011, so shortly after it, and I’ve just heard so many stories from people. It is still very real in lots of different ways, and with people all over the map in terms of their relationship to it, and strong feelings, and experiences. I think what you just brought up is so important to recognize, that to continue to use Paul’s metaphor of the body of Christ, that there is a lot of pain in the body, that there are wounds within the body, and some of those are self inflicted wounds. Some of those are wounds where one part of the body hurt another part of the body, maybe intentionally, maybe not. Maybe everybody thought that they were doing the right thing, and maybe they were, and they were unintended consequences.

Patrick Mason: You can spin this out lots of different ways. We have to acknowledge in ways that we’re not very good at, that there is real pain, and hurt, and loss, and betrayal, and grief within the body of Christ, not just because of outside enemies. That’s the way we framed it for a long time. It’s like, the good guys versus the bad guys, the outside versus the inside, and again, that’s why we circle the wagons. We have to recognize that we hurt each other too, and that sometimes even doing what we think is the right thing, has caused pain inside.

Patrick Mason: A couple of things. One, I think hopefully we can find ways to be honest, and to share that with one another, and then to do what our baptismal covenants call us to do, is to mourn with those who mourn, and comfort those who stand in need of comfort, that we don’t get to decide what their pain is, or say, “Oh, you have lung cancer, so I’m going to feel sorry for you. Oh, but you feel pain about your experience in the church? Sorry, I’m not going to mourn with you about that.” Our baptismal covenant does not allow us to be choosy in that way, so we have to do that.

Patrick Mason: Then the other thing is to recognize I think that … There’s the great quote from Joseph Smith where he talked about his own government of the church, but I think it’s the way that God leads the church as well, where he says, “I teach them correct principles and let them govern themselves.” I think we have to come to some peace with that, and what that really means, and then recognize that we are in this together. We’re all on this side of the bale, sort of fumbling about in more or less mists of darkness, all fumbling towards the tree. Can we do it together, even when we trip over one another, and then even bump into each other and cause pain for one another, can we pick each other up and can we do it together?

Tim Chaves: One thing I’ve been thinking about, Patrick, is my … If we want to use the term faith crisis, or at least when I went through a really trying time, that led to some kind of transition in my faith, it was different than Kate’s experience that she just related with Prop 8, but mine started a couple years after my mission when I read Rough Stone Rolling for the first time, which is a very aptly titled book. I think I saw these works, and these things that were in Joseph Smith’s life that I never expected, and I guess more generally if you were to look at the top five issues that people have when they go through the stereotypical faith crisis, I mean you could look at the book of Abraham, you could look at polygamy, you could look at quotes from Brigham Young, priesthood temple ban, LGBTQ issues.

Tim Chaves: I think a lot of times people will try to take each of those issues and attack it one by one, and try to figure out what’s my answer here, what’s my answer here, what’s my answer here, but the thread that sort of ties them all together, or it could be prophetic fallibility, and reliability, and not to say that, oh, they were wrong on all these things, I don’t think that’s the answer, but I think what was tough for me was I came into it with this naïve view that each of these things happened according to God’s will.

Tim Chaves: Eventually the dissidence became too much. If I allowed myself to think, well, you know, I get to decide what I think about that. There is potential that there was … that this wasn’t perfect, that these were imperfect men that set these things in motion, and that sort of unlocked a little bit of peace for me. It wasn’t perfect, but I stopped needing to, to some extent, just go after those issues really, really specifically and say, okay, there’s room for me to explore, and have an open mind about what’s happened here.

Tim Chaves: I think you relate in Planted, that you’ve spoken to many people that have maybe gone through those types of things, and asked those questions. I’m curious if you were to … Let’s say you were talking to somebody that was a few months in to discovering something in the church’s history that’s really bothering them, that’s caused a lot of dissidence or a lot of pain. What would you recommend to that person? How would you talk to them and would prophetic fallibility play a big role in what you would say?

Patrick Mason: Yeah, it would, because I think you’re right. At least I feel that for almost any of these issues that we’re talking about, there is an undercurrent of questions about, what does it mean to have and sustain living prophets. I think that’s the theological thread that connects virtually all of these issues. Elder [inaudible 00:52:07] talked about this recently, at the sense of kind of playing whack a mole, you solve one thing, but then another thing pops up. Unless you address the kind of underlying issues, and identify the underlying issue and then wrestle with that, then the presenting issues are going to keep popping up. Those are all real things.

Patrick Mason: In some ways, actually addressing the underlying issue, what it does though is it gives you a better foundation to address all of them when they pop up, so you’re not just doing them individually. One of the things that I think is so important is that people, they don’t feel a sense of shame or of guilt, or those kinds of things for asking these kinds of questions, that they need to remain confident in their ability to approach God for answers. Then also, that I think it’s really important that they continue to kind of lean into the spiritual practices that have got them to where they are at this point. It sounds like Pollyannaish, and we can just rattle off the Sunday School answers of pray, and go to church, and read Scriptures, and so forth. Those things are so essential actually, because it’s going to force you to pray in a different kind of way.

Patrick Mason: It’s not praying the same way you did when you were a 12 year old kid, or when everything was fine, but to dig deeper into your prayer life. You’re going to read Scriptures not in a peripheral, or a perfunctory way, but you’re going to dig deeper into them, and try to figure out, what are they really saying. Actually, when it comes to the matter of prophets, they say rather different things than what we often times assume, or teach in the church. Actually, I think they are the key to unlocking this puzzle in particular on prophets. The same with your church life. It’s not just going to be attending church in a perfunctory way, but it’s going to be digging in, and really thinking about what it means to be a part of a community, and what you’re getting out of it, what you’re giving.

Patrick Mason: Those things are so important. Then just to be patient with it. I talk in the book about, section 21, verse 5, that talks about following the words of the prophets in all patience and faith. Yeah, it takes faith to follow a prophet, but it also takes patience. I think patience is one of the hardest things for us to do, to sort of wait on The Lord, and to even wait on our own heart and mind, to kind of work these things out, because they are tough. Answers to very complex problems usually don’t come just overnight.

Kate: Something that I’ve … As you say that, just comes to me so strongly, is this idea that … For even in this conversation, reframing my relationship with the church to be that body of Christ that we’ve talked about over and over, really makes me think of the … What’s the word I’m looking for, well maybe the idea, or not the idea, the reality that we are in families that just, our nature of existence is situated in many little communities of individuals, like parents, for example that are calling a lot of the shots for our lives. At one point in your adolescence to adulthood, depending on your trajectory of development, realize one day that your parents are equally as messed up as everybody else, sometimes more, sometimes less, but that can be a very crazy experience as a young adult, teenager, wherever you are, 40 year old, whenever you realize that your parents aren’t perfect.

Kate: That creates in some ways this sense of panic for some people. I think for me, as I’ve figured out that, oh, my parents are experiencing the same experience that I am as a person, they’re going through their own things, but they have been such a guide for me, and I can be with them in this. I can be with them in this experience of learning, and maybe even thinking of the church in a similar way, of we’re all experiencing this. In some ways, that spiritual refinement that you talked about the prophets have, and that special witness, and that special call to be messengers, and how you kind of identified that I think is sacred, and is so special.

Kate: Maybe viewing it in that way of we are a family, not only just in the church, but as humans that are trying to make it through this, and seeking Christ with the prophets I think can be really valuable. One thing I wanted to I think put a little bit of focus on, and you touched on this in a way that really struck me, was that we’re all really just trying to make it through this together. We’re all stumbling, and we’re all figuring it out. I wonder for me, the idea of reframing the prophets to be imperfect but so valuable in our faith journey, has taken me to this place that I not only am able to say, okay, they’re imperfect but I’m going to live with it, but that that idea, that they although called specially to do a certain work, are equally as vulnerable to view their humanness as I am, but that God is still deeply willing to work with me on a daily basis.

Kate: That God is always coming back to me, always giving me another opportunity, and doing that with the prophets, and doing that with the body of Christ, and doing that with the family of humans that He’s created, and that not only is this frailty or fallibility of prophets a doctrine that maybe we can find some level of okay-ness with, but that it can actually help us feel the true and real grace of God, that that is really where the grace of God is, is in this struggle of frustration. That’s where God is. That’s where the grace is present.

Kate: For me it’s become … I hope it could be for us in some ways, one of my biggest testaments of the love of God.

Patrick Mason: Amen, amen, amen. I think that is it exactly. That we … Everything that you just said is exactly right, that we know that the way that this works in families, that our parents, that that is a holy and sacred calling, to be a parent to another human being, is incredible, no matter how messed up your parents are. You hope that … We know that there are really bad families, and dysfunctional families, and all that kind of stuff, and a lot of pain and grief, and so forth, but that there’s also something holy and divine about the family, however it’s construed.

Patrick Mason: We say this about the church, oh, the church must be true, or the missionaries would have ruined it a long time ago, or bishop, we say all these things. Right, and we know this is true, and I think the same is true about the prophets too, that what it all speaks to for me, is exactly what you just said, that this is about the grace of God, this is about the redemption of Christ, this is about the … We’re not Calvinists, and we sort of shy away from Calvinist language, but sometimes it’s just the best language in terms of the awesomeness of God.

Patrick Mason: That grace works in ways that are so unfathomable to us, especially as Mormons because we talk so much about work, and we’re so worried about our worthiness and all this kind of stuff, that sometimes we can obscure the grace of God. For me, that’s what all of this message is. For me, the message of the Old Testament is that God is going to choose His people, despite abundant evidence that they are so screwed up, and so unfaithful, and that they’re going to … Every time He tells them to go right, they’re going to go left, and that includes the prophets half the time. His grace and His love, and His kindness persist through all of it.

Patrick Mason: For me, this is all about how does Christ continue to redeem His people, and redeem His church. I think He’s established this church to do some special things in the world. I think He’s called us to do some special things in the world. Along the way we’re going to stumble and fall, but He will be there with His grace to redeem us throughout … That’s true for the prophets too. I think you put your finger exactly on it.

Kate: Thank you for speaking with us. I think that that, in my mind might be a good note to end on, and to hopefully sit with. I think a lot of the things we’ve talked about maybe have come for us through this journey, and there are individuals that are here, or here, or somewhere totally else on a different trajectory, and different wavelength, but hopefully this conversation can at least instill an idea that there’s expansive ideas to think about with prophets.

Patrick Mason: Yeah. I just want to say one more thing-

Kate: [crosstalk 01:01:48].

Patrick Mason: -’cause Tim had asked what other advice do you want to give. What you just said, that the people are at all different places, and when you’re sort of at the beginning of this, sort of wrestling with it for the first time, or maybe really in the thick of it, where it all seems like darkness, where it seems like only questions and your world is spinning, it’s so disorienting, and it’s hard to know what to do, and kind of the last piece of advice I give to people is to hold onto hope. It is a gospel of hope. God is a God of hope. One of my favorite quotes is from Martin Luther King, he says, “The moral arch of the universe is long, but it bends towards justice.”

Patrick Mason: The nature of the atonement, the nature of believing in God means that you believe that there is a better future out there. You believe that God can control the destiny of the world, and the destiny of your life to make for better things. Just don’t let go of hope, that even when things, look, were so tough to rely on, and people who have maybe gotten a little further in the process, and hold on to that, and just hold on to hope that God can see it through, even when you’re not sure how, or when, or where that could happen. Continue to hold on to hope.

Tim Chaves: The thing is to me too, the main message that we’ve received from the prophets is to hold onto hope. That hope really that we have as members of the church, is in Jesus Christ. I picture the analogy of like a painting, and if you look really, really closely there may be imperfect brush strokes, and you don’t know how the whole thing got created, but if you take a few steps back, you can see a beautiful work of art. I think the beautiful work of art that the prophets have created over time is this … pointing to Jesus Christ, who loved us unconditionally, perfectly, and was able to experience our woundedness, our difficulties, our trials, including the ones that we are going through when we have struggles in our faith.

Tim Chaves: The message that we should be receiving, perhaps rather than looking at all the little imperfections, all those little brush strokes, take a step back and say, “There is reason to hope.” I think that’s really the message that I try to focus on, even though at time it is difficult to get away a little bit from the minutiae.

Kate: Yeah. How beautiful that we have prophets that are such powerful witnesses of that, of Jesus Christ. That’s really what it’s about. Thank you Patrick, for being here, Tim, for being here. I’m grateful to have been here.

Tim Chaves: Thank you, Kate.

Kate: You’re always here, so thank you for that. Yeah, thank you.

Patrick Mason: All right, thanks.